The Spirits of Maguey

Nov 2004

Citation: Erowid F. "The Spirits of Maguey". Erowid Extracts. Nov 2004;7:12-15.

|

It's nearly impossible to visit Oaxaca and not encounter one of the many small shops selling

mezcal, a distilled alcoholic beverage made from plants of the genus Agave, which has a long history

of use in Mexico.

A young woman usually stands near the open doorway of the shop, tucked behind a small counter displaying four or five varieties of the house brand. These are lined up carefully next to a stack of small cups, a clear invitation for free samples. Behind her is a wall full of bottles ready for purchase.

This scene is repeated over and over throughout Oaxaca City and the surrounding villages. In the city itself, the shops are most heavily concentrated in an area south of the city center, while a highway to the southeast of the town acts as the main location of small production "factories".

Part of our explicit purpose in visiting Mexico was to learn about the local psychoactives. Since we were attending a conference in Oaxaca City, our first week would be spent in and around the busy town. Jonathan Ott would be presenting a talk about mezcal later in the week, so in preparation, we delved into the history of the drink and began our quest for the perfect bottle.

A young woman usually stands near the open doorway of the shop, tucked behind a small counter displaying four or five varieties of the house brand. These are lined up carefully next to a stack of small cups, a clear invitation for free samples. Behind her is a wall full of bottles ready for purchase.

This scene is repeated over and over throughout Oaxaca City and the surrounding villages. In the city itself, the shops are most heavily concentrated in an area south of the city center, while a highway to the southeast of the town acts as the main location of small production "factories".

Part of our explicit purpose in visiting Mexico was to learn about the local psychoactives. Since we were attending a conference in Oaxaca City, our first week would be spent in and around the busy town. Jonathan Ott would be presenting a talk about mezcal later in the week, so in preparation, we delved into the history of the drink and began our quest for the perfect bottle.

Agave #

Agave (uh-GAH-vay) plants resemble spiky spheres with long, thick, fleshy leaves growing in a

rosette pattern. They range from a few inches to more than 12 feet in diameter. Agave are sometimes

confused with cacti or succulents, but they belong to their own family called Agavaceae.

With only a few exceptions, Agave plants flower only once, after which they die. Their English common name, "century plant", comes from the mistaken belief that the plant grows for 100 years before flowering. In truth, smaller Agave species may flower after only 3–4 years, while larger species may take 40–50 years. The flowers grow on a single large stalk that sprouts out of the middle of the plant and may grow up to 15 feet tall.

Agave are native to Central and North America. They are found from Alberta, Canada in the north to Venezuela and Columbia in the south,1 but grow best at 4000–8000 feet above sea level. Experts seem to disagree on exactly how many species of Agave exist, but there are over 130 that grow in Mexico alone.1,2,3

In the Náhuatl language of the Aztec, the Agave plant was known as metl or mexcalmetl, the

latter being the origin of the word mezcal. The term maguey (mah-GAY)-- believed to have originated

in the Greater Antilles but introduced into Mexico by the Spanish--is still the common name used

throughout Mexico today.4

Agave, like hemp, is touted as a "miracle plant" for its many uses. Its fibers were used by the Aztec to make clothing, rope, and other textiles; it was a source of food, water, intoxicating beverage, medicine, soap, glue, paper, and thread; its leaves were used in roofs and fences; and its spines were turned into weapons, tools, and sewing needles.5

Because of its utility, Agave holds a place of esteem in traditional Mexican culture. Baron Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian explorer and naturalist of the early nineteenth century, described maguey as "the most useful of all the crops that nature has granted the people of North America", and Linnaeus granted it the Latin name "Agave" meaning "admirable" or "noble".6

With only a few exceptions, Agave plants flower only once, after which they die. Their English common name, "century plant", comes from the mistaken belief that the plant grows for 100 years before flowering. In truth, smaller Agave species may flower after only 3–4 years, while larger species may take 40–50 years. The flowers grow on a single large stalk that sprouts out of the middle of the plant and may grow up to 15 feet tall.

Agave are native to Central and North America. They are found from Alberta, Canada in the north to Venezuela and Columbia in the south,1 but grow best at 4000–8000 feet above sea level. Experts seem to disagree on exactly how many species of Agave exist, but there are over 130 that grow in Mexico alone.1,2,3

|

Agave, like hemp, is touted as a "miracle plant" for its many uses. Its fibers were used by the Aztec to make clothing, rope, and other textiles; it was a source of food, water, intoxicating beverage, medicine, soap, glue, paper, and thread; its leaves were used in roofs and fences; and its spines were turned into weapons, tools, and sewing needles.5

Because of its utility, Agave holds a place of esteem in traditional Mexican culture. Baron Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian explorer and naturalist of the early nineteenth century, described maguey as "the most useful of all the crops that nature has granted the people of North America", and Linnaeus granted it the Latin name "Agave" meaning "admirable" or "noble".6

The first full day of conference talks fell on September 15th, the day before Mexican Independence

Day. Mexican Independence Day is similar to the 4th of July in the United States, with the

celebration beginning at 11 PM the evening before. The city was decorated with colored lights and

flags for the event, and after a short ceremony in the zocalo (town center), the crowd erupted into

a rowdy fiesta with fireworks, confetti, whistles, and colored shaving cream that was sprayed

aggressively on everything and everyone in sight.

A group of conference attendees met up in a sidewalk bar/café at the edge of the zocalo where we sat to watch the chaos. We ordered several shots of mezcal each (between $1.50 and $4.00 for a shot), experimenting with different brands and styles. They varied significantly from one to the next: some were sharp and nearly undrinkable, some smooth with an almost silky mouth-feel, and perhaps the best had a distinct smoky taste.

Everyone got appropriately tipsy during our first encounter, but we wondered where this stuff came from. We knew what Agave plants looked like, but it wasn't at all obvious how one would produce alcohol from such a plant.

A group of conference attendees met up in a sidewalk bar/café at the edge of the zocalo where we sat to watch the chaos. We ordered several shots of mezcal each (between $1.50 and $4.00 for a shot), experimenting with different brands and styles. They varied significantly from one to the next: some were sharp and nearly undrinkable, some smooth with an almost silky mouth-feel, and perhaps the best had a distinct smoky taste.

Everyone got appropriately tipsy during our first encounter, but we wondered where this stuff came from. We knew what Agave plants looked like, but it wasn't at all obvious how one would produce alcohol from such a plant.

Aguamiel #

"I break up the maguey. I pierce the

center. I pierce the stalk. I clean the

surface. I scrape it. [...] I remove the

maguey syrup from each one. I heat

the maguey syrup. I make wine."

-- The Florentine Codex (c. 1580)

The leaves of the Agave grow on a short stalk, the base of which is called a piña--picture a

huge pineapple growing underground with only the top leaves emerging from the surface. The species

used most frequently in the production of alcohol grow for 8 to 15 years before they show signs of

flowering. 3 At this point, the leaves are cut

from one side of the plant to allow access to the heart. In a process called "castration", a hole is

carved into the top of the piña where the flower would have grown and the heart of the plant

is removed.

The hole is left full of plant material and scrapings for a month or more before it is cleaned out and the sides of the hole rescraped.3 The nourishment which the plant would have used for the huge flower then begins to seep from the sides and gather in the newly created depression as a sweet sap called aguamiel (necutli in Náhuatl).1 The aguamiel is collected from the piña by the tlachiquero, who scoops or sucks it out with a long tube up to three times a day for several months. 3.7 During that time, the plant produces three to four liters of this nectar each day.3

Aguamiel can be harvested and consumed straight or used as the source of a number of beverages. Atole, for example, is a nonalcoholic beverage made from hot cornmeal and unfermented aguamiel.

The hole is left full of plant material and scrapings for a month or more before it is cleaned out and the sides of the hole rescraped.3 The nourishment which the plant would have used for the huge flower then begins to seep from the sides and gather in the newly created depression as a sweet sap called aguamiel (necutli in Náhuatl).1 The aguamiel is collected from the piña by the tlachiquero, who scoops or sucks it out with a long tube up to three times a day for several months. 3.7 During that time, the plant produces three to four liters of this nectar each day.3

Aguamiel can be harvested and consumed straight or used as the source of a number of beverages. Atole, for example, is a nonalcoholic beverage made from hot cornmeal and unfermented aguamiel.

Late one evening, after the conference had ended for the day, we hopped into a cab and asked the driver to take us to an open bar. We were dropped off in front of a small, dimly-lit establishment called Tabuki. Several small tables were spaced along the edges of the dark room occupied by groups of two or three patrons. One couple danced to loud techno music spun by a DJ at the other end of the room.

We sat down at the bar and asked the bartender for a drink menu. After somewhat randomly selecting

a collection of mezcals from the menu we ordered one "con chile", one "reposado" and two "escorpion".

All were reasonably good, but we preferred the escorpion. The next round we tried "con limon" and

"gusano" and found a preference for the gusano; the third round we decided to try a "cedron".

As the bartender pulled down the cedron bottle we saw that it contained an herb-like stick inside, much as a bottle of specialty olive oil might contain a rosemary branch. Looking up at the shelf behind the bar we realized that each of the bottles contained something: the "gusano" contained a worm, the "con chile" had two small hot looking chile peppers, the "limon" had a full half of a lemon, and...oh shit...the "escorpion" bottle contained two large, black, nasty-looking scorpions.

With only one Spanish speaker in our group (and a non-native speaker at that) the titles had seemed more like brand names than descriptions. It took us a few minutes to get used to the idea of drinking liquor with scorpions soaking in it, but with mezcal-reinforced courage, we proceeded to polish off the bottle. When asked whether anyone ever ate the scorpions, the bartender answered, "sometimes, if they're drunk enough."

|

As the bartender pulled down the cedron bottle we saw that it contained an herb-like stick inside, much as a bottle of specialty olive oil might contain a rosemary branch. Looking up at the shelf behind the bar we realized that each of the bottles contained something: the "gusano" contained a worm, the "con chile" had two small hot looking chile peppers, the "limon" had a full half of a lemon, and...oh shit...the "escorpion" bottle contained two large, black, nasty-looking scorpions.

With only one Spanish speaker in our group (and a non-native speaker at that) the titles had seemed more like brand names than descriptions. It took us a few minutes to get used to the idea of drinking liquor with scorpions soaking in it, but with mezcal-reinforced courage, we proceeded to polish off the bottle. When asked whether anyone ever ate the scorpions, the bartender answered, "sometimes, if they're drunk enough."

Pulque #

Several intoxicating liquors are made from Agave.

The most traditional was called octli poliqhui in Náhuatl, which

became pulque (POOL-kay) in Spanish. The finest quality pulque was

called teooctli or "the octli of the Gods".1

Pulque is a milky, foamy and viscous beverage created by fermenting the aguamiel of the Agave. It

is sometimes called "maguey wine" or "agave wine" and can be produced from a number of different

Agave species. After aguamiel is collected, it is allowed to ferment for about 10 days with

naturally occurring yeasts. The resulting material is then used as a starter for further batches of

pulque. A small amount is added to fresh aguamiel, kickstarting the fermentation process and

allowing ready-to-drink pulque to be created in a day or two.

Young pulque is called Tlachique, or pulque dulce, a sweet beverage with an alcohol content of only 2-4%. Regular pulque is 4-8% alcohol. Waiting a little longer produces Pulque fuerte, which is stronger and more sour. Pulque lasts only a few days before becoming too sour to drink. Pulque is believed to have been used for 2,000 years or more in the central highlands of Mexico.8 During this time, the beverage became an important social and cultural force. It is a nutritious beverage, rich in vitamins, that had many medicinal uses.5 According to the Florentine Codex, it was also used ceremonially during harvests, marriages, births, and burials and is linked to many myths and deities.

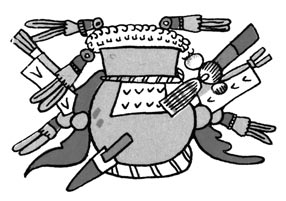

According to one such myth, the woman who discovered the method of cutting the Agave piña, collecting the aguamiel and fermenting it was named Mayahuel. One day, Mayahuel, a farmer's wife, was chasing rabbits away from a field of Agave. As she was doing this, she noticed that one rabbit didn't run and instead staggered in circles around her, acting as though it were happy and not afraid. The rabbit had been eating from the heart of an Agave plant and drinking its juice. She told her husband about this and they collected some of the aguamiel in a jar, which they put in their house as they went back to work. After finishing for the day they returned home and drank the juice, which made them feel like the rabbit had: happy, fearless, and then sleepy. Because of this discovery, Mayahuel was made the goddess of the maguey and is depicted by the Aztecs sitting in the middle of a maguey plant, often with a rabbit nearby.

Pulque was considered a gift from the gods, and as such it honored the gods to drink it. On holy days such as the Day of the Dead, people were expected to drink pulque and become intoxicated, but aside from these special occasions public drunkenness was forbidden. This rule was strictly enforced; public intoxication could be severely punished with stoning or hanging except in the case of the elderly. 9

Other intoxicating plants and herbs were sometimes added to pulque; the word ocpatli was used to

describe these mixtures. 1 The Spanish are said to

have banned at least one of the admixture components, a bark (possibly Acacia) that made the pulque

more intoxicating. In more recent times, pulque drinking centered around the pulquería, a

community establishment where people gathered to drink. At one time pulquerías were an

integral part of local culture, yet they have diminished in popularity over the last 100 years. In

1870 there were more than 822 pulquerías in Mexico City alone, while in 1998 there were

fewer than 80.3

|

Young pulque is called Tlachique, or pulque dulce, a sweet beverage with an alcohol content of only 2-4%. Regular pulque is 4-8% alcohol. Waiting a little longer produces Pulque fuerte, which is stronger and more sour. Pulque lasts only a few days before becoming too sour to drink. Pulque is believed to have been used for 2,000 years or more in the central highlands of Mexico.8 During this time, the beverage became an important social and cultural force. It is a nutritious beverage, rich in vitamins, that had many medicinal uses.5 According to the Florentine Codex, it was also used ceremonially during harvests, marriages, births, and burials and is linked to many myths and deities.

According to one such myth, the woman who discovered the method of cutting the Agave piña, collecting the aguamiel and fermenting it was named Mayahuel. One day, Mayahuel, a farmer's wife, was chasing rabbits away from a field of Agave. As she was doing this, she noticed that one rabbit didn't run and instead staggered in circles around her, acting as though it were happy and not afraid. The rabbit had been eating from the heart of an Agave plant and drinking its juice. She told her husband about this and they collected some of the aguamiel in a jar, which they put in their house as they went back to work. After finishing for the day they returned home and drank the juice, which made them feel like the rabbit had: happy, fearless, and then sleepy. Because of this discovery, Mayahuel was made the goddess of the maguey and is depicted by the Aztecs sitting in the middle of a maguey plant, often with a rabbit nearby.

Pulque was considered a gift from the gods, and as such it honored the gods to drink it. On holy days such as the Day of the Dead, people were expected to drink pulque and become intoxicated, but aside from these special occasions public drunkenness was forbidden. This rule was strictly enforced; public intoxication could be severely punished with stoning or hanging except in the case of the elderly. 9

|

At the end of the conference, a day-trip was organized for 50 or so participants who piled into a

bus and headed out on a tour of local sights. After visiting the ruins at Mitla and stopping at the

"world's largest tree" in Tule, we arrived at a small mezcal factory that sat directly alongside

the main road. Though the term "factory" brings to mind large warehouses filled with expensive

specialized equipment, this, like most in Oaxaca, was a small operation.

We were taken on a quick tour of the production process in the yard out behind the building, where we had the opportunity to taste a little of the unfermented Agave piña, wet with aguamiel. It was sweet and candy-like--in fact we were told it is often given to children as a sweet treat. After the tour we were brought up to the tasting bar and encouraged to buy a bottle or two. Though the visit was rather rushed and the large crowd made it difficult to ask questions, it whetted our appetite for learning more about production.

We were taken on a quick tour of the production process in the yard out behind the building, where we had the opportunity to taste a little of the unfermented Agave piña, wet with aguamiel. It was sweet and candy-like--in fact we were told it is often given to children as a sweet treat. After the tour we were brought up to the tasting bar and encouraged to buy a bottle or two. Though the visit was rather rushed and the large crowd made it difficult to ask questions, it whetted our appetite for learning more about production.

Mezcal #

|

Mezcal (from the Náhuatl mexcalmetl) is considered a "mestizo" drink, a combination of the

indigenous pulque and the distillation process brought by the Spanish. Distillation was unknown in

Mexico before the Spanish conquest. Mezcal is traditionally a single distillation of pulque (its

more famous cousin, tequila, is a double-distilled variety of mezcal made from a specific type of

Agave: see sidebar.) But rather than using aguamiel, the modern production process involves

chopping the leaves from the piña and removing the entire thing from the ground. The

piña is cut into halves or quarters and placed into a rock-lined conical pit (called a

palenque) about 12 feet in diameter and 8 feet deep. The piñas are then covered with glowing

rocks that have been heated in a wood fire. The entire pile is covered with plant fibers and a

layer of earth, then left to bake for two to three days, adding a distinct smoky flavor to the final

product.

After baking, the piñas are removed from the pit and placed in a large stone circle, where they are ground with a horse- or donkey- pulled millstone. Once they are ground to a fibrous pulp, they are placed in large uncovered wooden vats, where they sit fermenting with their own natural yeasts for several days. At this point, water is added and the mixture is allowed to sit for another several days.

The mash is then transferred in small quantities to a nearby still, where it undergoes the distillation process; the resulting liquid is mezcal, an 80 proof (40%) alcohol. Some mezcal is single distilled while some manufacturers perform a second distillation. Singledistilled varieties retain more of the signature smoky flavor.

This production process was developed during the early sixteenth century. Unfortunately, the introduction of distilled alcohol in the sixteenth century, combined with the changes brought about by the conquest, resulted in rampant alcoholism among the Aztec. In 1785, the Spanish banned the manufacture of alcoholic beverages in "New Spain", a ban which lasted 10 years.

After baking, the piñas are removed from the pit and placed in a large stone circle, where they are ground with a horse- or donkey- pulled millstone. Once they are ground to a fibrous pulp, they are placed in large uncovered wooden vats, where they sit fermenting with their own natural yeasts for several days. At this point, water is added and the mixture is allowed to sit for another several days.

The mash is then transferred in small quantities to a nearby still, where it undergoes the distillation process; the resulting liquid is mezcal, an 80 proof (40%) alcohol. Some mezcal is single distilled while some manufacturers perform a second distillation. Singledistilled varieties retain more of the signature smoky flavor.

This production process was developed during the early sixteenth century. Unfortunately, the introduction of distilled alcohol in the sixteenth century, combined with the changes brought about by the conquest, resulted in rampant alcoholism among the Aztec. In 1785, the Spanish banned the manufacture of alcoholic beverages in "New Spain", a ban which lasted 10 years.

During our second week in Oaxaca we took a day to drive out to the mezcal producing area southeast

of Oaxaca City. We spent some time photographing fields of Agave and visited a second mezcal

factory as well as a handful of small mezcal shops.

There we learned more about the types of mezcal. We tasted four different varieties and decided we liked the second most expensive one the best. We tried to haggle with the shopkeeper, but his response was "If you want it to be cheap, then buy the cheap stuff." The "cheap stuff" was a clear harsh alcohol that tasted like moonshine--not the smooth variety we were seeking.

There we learned more about the types of mezcal. We tasted four different varieties and decided we liked the second most expensive one the best. We tried to haggle with the shopkeeper, but his response was "If you want it to be cheap, then buy the cheap stuff." The "cheap stuff" was a clear harsh alcohol that tasted like moonshine--not the smooth variety we were seeking.

Varieties #

|

Once the mezcal has been distilled, there are several different varieties that can be produced.

"Blanco", "silver" or "white" (the cheap stuff) is either not cask-aged or aged for only a short

period. It has a sharper and simpler flavor. "Reposado" is cask- aged for between two months and

one year, while "añejo" is cask- aged for more than a year. Cask aging darkens the color and

adds an oakey flavor that tempers the harshness of a young mezcal.

There are two types of larvae; the red, which inhabit the piña of the Agave, and the white, which inhabit the leaves. Both are used in modern mezcal production. These days, dozens of larvae may be added to reposado or añejo mezcal as they age in oak casks, imparting even more of their flavor-smoothing qualities. In the end, a single larva is then added to the bottle to help identify it as gusanito. However, contrary to popular lore, there are no worms or larvae in bottles of Mexican tequila. There are strict Mexican laws about what substances are allowed in tequila, and worms are not one of them.

There are also stories about mezcal or tequila "worms" being psychoactive. Some mistakenly claim they lend extra psychoactive properties, while others insist there is no effect on the mezcal at all. Most experts agree that the larvae have a distinct effect on taste, but no mind-altering properties.

Gusanito - the "worm" #

Another common variety is gusanito, or "the little worm". There are plenty of rumors about the worm

in mezcal (or tequila) bottles. Actually, it's not technically a worm, but a caterpillar--the

larval stage of the Hipopta agavis butterfly. The larvae are a common pest in the Agave piña.

Because piñas are used whole (including the larvae inside), the larvae are a common,

incidental ingredient. The larvae (or gusanos in Spanish) are a source of protein that has been

eaten by the people of Mexico since before the Spanish conquest. They are still eaten today as a

fried snack. It wasn't until the 1940s, though, that a mezcal producer named Jacobo Losano Paez,

realizing that the larvae imparted a smoother taste to the mezcal, decided to market a specific

"gusanito" variety.10There are two types of larvae; the red, which inhabit the piña of the Agave, and the white, which inhabit the leaves. Both are used in modern mezcal production. These days, dozens of larvae may be added to reposado or añejo mezcal as they age in oak casks, imparting even more of their flavor-smoothing qualities. In the end, a single larva is then added to the bottle to help identify it as gusanito. However, contrary to popular lore, there are no worms or larvae in bottles of Mexican tequila. There are strict Mexican laws about what substances are allowed in tequila, and worms are not one of them.

There are also stories about mezcal or tequila "worms" being psychoactive. Some mistakenly claim they lend extra psychoactive properties, while others insist there is no effect on the mezcal at all. Most experts agree that the larvae have a distinct effect on taste, but no mind-altering properties.

| Tequila vs Mezcal |

|

Tequila and mezcal are very similar beverages that are distinguished by production process and

taste. Mezcal is the broader term for a distilled alcoholic beverage made from the juice of the Agave

plant. Though tequila is better known outside of Mexico, it is technically a type of mezcal. There are a few differences between tequila and mezcal:

|

The idea of a worm in the bottle was a little repulsive, especially to our delicate vegetarian

palettes. But after learning that the larva is actually a native inhabitant of the plant that also

serves to add flavor and smoothness, we were able to agree that the gusanito was our favorite.

We bought several bottles to bring home before deciding that the escorpion was too novel to pass up. We returned to the bar to buy a bottle and now have our very own pickled scorpion in the cabinet.

We were a little afraid about the reaction of customs officials to these unsealed bottles of amber liquid with scorpions in the bottom, but happily we never found out.

Spending a couple of days learning about mezcal left us with a desire to visit Oaxaca again when we could devote more time to studying pulque, Agave cultivation, and the finer details of the mezcal production process. Even this would barely scratch the surface of the many ways that Agave has impacted the people and culture of Mexico. We look forward to our next trip.

We bought several bottles to bring home before deciding that the escorpion was too novel to pass up. We returned to the bar to buy a bottle and now have our very own pickled scorpion in the cabinet.

We were a little afraid about the reaction of customs officials to these unsealed bottles of amber liquid with scorpions in the bottom, but happily we never found out.

Spending a couple of days learning about mezcal left us with a desire to visit Oaxaca again when we could devote more time to studying pulque, Agave cultivation, and the finer details of the mezcal production process. Even this would barely scratch the surface of the many ways that Agave has impacted the people and culture of Mexico. We look forward to our next trip.

References #

- Ott J. Lecture on Maguey. Mind States Conference. Oaxaca, Mexico. Sep 2004.

- Mohr GM. "Blue Agave and Its Importance in the Tequila Industry." Ethnobotanical Leaflets. Fall 1999. http://www.siu.edu/~ebl/

- Maguey. Artes de Mexico, No 51. 2000.

- Chadwick I. "Tequila: In Search of the Blue Agave." Accessed Oct 21, 2004. http://www.ianchadwick.com/tequila/

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex. Trans. A.J.O. Anderson and C.E. Dibble. School of American Research, 1978.

- Márquez JQ. Mezcal: Origin, Elaboration and Recipes. Universidad José Vasconcelos de Oaxaca, 1997.

- de Barrios VB. A Guide to Tequila, Mezcal, and Pulque. Minutiae Mexicana, 1971.

- What is Pulque? Accessed Oct 21, 2004. http://www.mezcal.com/pulque.html

- Madsen W, Madsen C. "The cultural structure of Mexican drinking behavior." Q J Stud Alcohol. Sep 1969; 30(3). Kolendo J. "The Agave: A Plant and its Story."Accessed Oct 20, 2004. http://globalnet.co.uk/~jankol/articles/ Document Re-Found Apr 2010: http://www.desert-tropicals.com/Articles/Agave/index.html

Photo Credits #

- Agave plant from Mitla ruins. Photo by Erowid. Tlacolula, Mexico. Sep 2004.

- Mayahuel. Códice Laud. Antigüedades de México. 1964; 3:363.

- Decorative pulque pot. from Codex Borgia. in Longhena M. Maya Script. Abbeville Press, 2000.

- Agave piñas. Photo by Erowid. Tlacolula, Mexico. Sep 2004.

- Pit for baking piñas. Photo by Erowid. Tlacolula, Mexico. Sep 2004.

- Mezcal after distillation. Photo by Erowid. Tlacolula, Mexico. Sep 2004.

- Millstone. Photo by Erowid. Tlacolula, Mexico. Sep 2004.