He Spoke for the Plants

Remembering Dale Pendell

v 1.0 - Mar 2018

Citation: Hanna J. "He Spoke for the Plants: Remembering Dale Pendell". Erowid.org. Mar 2018. Online edition: Erowid.org/culture/characters/pendell_dale/pendell_dale_remembrance1.shtml

When Theodor Seuss Geisel [Dr. Seuss] passed away in 1991, a TV news reporter asked his widow about the renowned artist-author's legacy. After relating how important literacy was to her husband, she emphatically concluded, "More than anything, he would have wanted to be remembered as someone who helped to make the world a more literal place." Simultaneously cringing and laughing, I hoped that the good "Dr." wasn't rolling in his grave. I'd like to believe that the news team's editor figured that her slip of the tongue would provoke a smile in viewers who appreciated irony and didn't expect anyone grieving the death of a loved one to be in top form.

In general, I am not a fan of poetry. But within the child-sized handful of poets whose works I enjoy, Dr. Seuss tops the list. Coming in close second is Dale Pendell. And so it was that—a couple of years ago—I shared the tale of dame Seuss's faux pas with Dale. I wanted to let him know how much I had appreciated his poetry over the past couple of decades, a point made all-the-more heartfelt by emphasizing the extremely fine (and discriminatingly small) company that I considered him to keep. Along with the works of Seuss, Dale's poems had redeemed an entire category of literature for me.

I first met Dale in the early 1990s, as I was forging a few of my first paths toward the psychedelic community. This was during a pivotal period of content communication in the psychedelic scene. Personal computers were becoming increasingly ubiquitous. Electronic bulletin boards and e-mailing lists provided forums for the creation of virtual special-interest groups with contributions from globally disparate members. Daily discussions offered opportunities for friendships to form between (often pseudonymous) individuals who'd never interacted in person. Such folks sometimes eventually got together at "flesh meets".

Prohibitionist propaganda had dominated drug data discourse and distribution during the 1980s. As the 1990s began, however, a few intrepid authors—some via their own independent desktop publishing efforts—provided the crucial kick-starts that helped ignite the engine of the Entheogenic Reformation.

Instant classics from this period include Sasha and Ann Shulgin's PIHKAL (1991) and TIHKAL (1997), Terence McKenna's The Archaic Revival (1991) and Food of the Gods (1992), Jim DeKorne's The Entheogen Review (1992) and Psychedelic Shamanism (1994), Jonathan Ott's Pharmacotheon (1993/1996), and Dale Pendell's Pharmako/Poeia (1995). These publications shared a common thread: each detailed scientific research that could be considered to have been prohibited by the government. Primarily occurring underground, the "Large Animal Bioassays" reported on in these texts were conducted by the publications' authors, their colleagues, and assorted anonymous or pseudonymous amateurs—kitchen chemists and basement shamans bold enough to experiment on their own bodies in pursuit of greater knowledge, and brave enough to share what they learned with others, while navigating a dangerous legal landscape that valued control culture over liberty and basic human rights. As McKenna aptly noted of the times, "...Western tradition has a built-in bias against self-experimentation with hallucinogens. One of the consequences of this is that not enough has been written about the phenomenology of personal experiences with the visionary hallucinogens."1

All of these bioassayists were wordsmiths, producing books packed with intelligent, insightful information. However, the poetic "poison path" peculiar to Pendell's plantastic Pharmaco/ publications stood apart. Mentation accessed via psychedelics is commonly characterized as being impossible to adequately describe: by its nature, it's ineffable. While this may well be true, if there was anyone who could "F" the in-F-able, it was Dale.

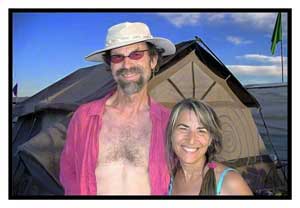

At Burning Man, the site of many first flesh meets, I spotted Dale sitting cross-legged under a PVC dome. On top of a cloth spread out in front of him, he was arranging a stack of leaves, a small pot of white powder, some other containers filled with various botanicals, and a few handfuls of what looked like over-round walnuts. He wielded what appeared to be an oddly designed metal nutcracker; extending down for a couple of inches from the fulcrum on the inside of the handles it had a slicing blade. I watched Dale struggle somewhat to push the blade repeatedly through one of the orbs, reducing it to thin slices. Realizing that I'd been staring, I asked: "Whatcha got there?"

"This is the traditional tool used to prepare these," he informed me through grunts of exertion, "but they are substantially softer and easier to slice when they're greener and not so dried out." He placed some of the slices onto one of the leaves, and added a few pinches of flavor-enhancing herbs topped off with some of the white power, which turned out to be either lime or baking soda (I can't recall). Despite having read that betel nut is one of the most popular stimulants worldwide, I had never previously come across it. Dale seemed to have a knack for obtaining obscure psychoactive plants.

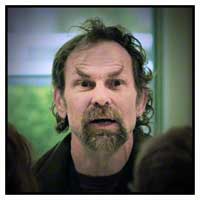

Dale was a wild man. Dale was a gentleman. On first encountering his electrified caterpillar eyebrows, one might wonder if he was in league with the Devil. Such concerns vanished upon spotting the ever-present twinkle in his eyes, which instantly spilled the beans... they were, in fact, the Devil's eyebrows. Dale had pinched them on a dare while the great beast was napping. It wasn't as reckless as you might think. Dale understood that he'd have to poison a well from time to time.

Dale was a green man, a plant man, a gardener. A back-to-nature man. A leave-no-trace man. A tree hugger. And a carpenter. A builder of fires. He embodied the D.I.Y. ethic. He was a scientist. A software developer. A singer of song. An artist, activist, peacenik, and an Anarchist. An ethnobotanist, an herbalist, a crafter of elixirs and tonics, extractions and distillations. He made small batches, on his own Green Fairy label Pharmako Botanikos, of the finest wormwood-based elixir, which he generously shared with friends. His firewater conveyed an herbaceous bitterness unlike anything else; it truly had to be experienced to be appreciated.

He loved literature and was probably the most well-read individual I've had the pleasure of knowing. Shooting the shit with Dale provided access to an endless supply of intriguing information and entertaining escapades. It was a bit like having a conversation with the eponymous character from My Dinner with Andre, although Dale was much more mellow. His spoken and written words had a profound effect on my life, and the lives of numerous others.

Now Dale was no slouch as a self-experimentalist, and at times his efforts occurred along the cutting-edge of contemporary research. Consider, for example, his work with the Mazatec magic mint, an enigmatic entheogen indigenously identified as Ska Pastora. Dale had been growing and studying the plant since 1985. As an early (non-native) investigator actually able to ascertain activity from Salvia divinorum, he could count himself among a relatively small group of people who had ingested the plant via the non-traditional method of smoking its leaves. In 1992, he remarked:

Siebert's paper confirmed Dale's speculation: the plant's primary psychoactive component was incredibly potent. Leading researchers in the field contemplated what sort of proactive action might be taken to reduce the chance that the plant and/or its active compound would fall victim to prohibitive legal restrictions. Consensus was that authors writing texts on the topic should focus on effective ways that people might use the whole plant or simple/crude extractions, instead of fostering the use, production, or distribution of salvinorin A in its pure form as a crystalline white powder. Dale did just that within the Salvia section of Pharmako/Poiea.

He encouraged newbie Salvianauts to begin their relationship with Ska Pastora by first cultivating and harvesting the plant; fresh leaves could be administered buccally as a quid, while plain dried leaf could be smoked in a pipe. After discouraging his readers from choosing the "crystal highway" as their path for this poison, he went on to describe a crude alcohol-based extraction process for yielding a "4X" material, formulated at this level so that it was possible for individuals without access to a milligram scale to safely "eyeball" a dose.

Since that chapter was published, knowledge of Salvia has increased worldwide and the plant has seen a substantial rise in the number of people who have tried it once or who take it occasionally. This heightened awareness may be partially attributable to the bizarre pop culture phenomenon of Salvia trip videos to YouTube, which neither Dale nor anyone else could have predicted. Within the realm of literature, on the other hand, Pendell's Pharmaco/Poeia has become established as a primary topical reference, commonly quoted from or cited in articles and books focused on Salvia divinorum.

Pendell was able to creatively employ a "plant's eye" viewpoint—whether it acted as a muse or a foil—in order to foster a dialogue with the sort of unusual inner voices that one hears at times during altered head spaces. Concern over whether or not the existence of "plant spirits" (or other associated "discarnate entities" that similarly cluster around the edges of altered consciousness) could ever be empirically proven to be "real" became less compelling. Things like increased access to artistic expression, improved introspective self-awareness, and an enhanced ability for viewing any situation from novel and unfamiliar perspectives that inspired increased empathy now seemed more important. His inclusion of conversations with plant spirits allowed him to evoke a more accurate representation of the psychic terrain traversed by increasing the color of language through poetic abstraction.

Dale was more than a gifted poet. His well-rounded works of prose beautifully balanced visionary insight, wry humor, scholarly detail, arcane references, practical wisdom, descriptive asides, important questions, and an impressive clarity of expression. His dedication to fundamental traditions of text was exemplified in his effort to compile and self-publish a separate bookletted Index for Pharmaco/Poeia, when the publisher failed to include one within the book itself.

A couple of times, I was charged with the responsibility to edit articles of Dale's published in The Entheogen Review and Erowid Extracts. It was easy work. Out of all of the texts I've edited over the years, Dale's required the least corrections and garnered the fewest suggestions for alterations. His writing blended style and substance with a page-turning force that was unquestionably all his own.

In 2014, a diagnosis of liver cancer caused Dale to sound a clarion call in search of a prospective donor for a liver transplant. A generous individual kindly volunteered, and the surgery occurred in March of 2015. At a gathering a year later, his friends felt overwhelming gratitude to the liver donor, who was present, for the gift he'd given to Dale and to all of us, by buying Dale some more time.

Dale continued to write for as long as he could. Near the end, when he was no longer able, he remarked: "The pain outran the pen."

True enough. Yet even so, in the big picture, I think that Dale's pen was mightier. For without a doubt, Dale will be remembered as someone who helped to make the world a more literate—and poetic—place.

In general, I am not a fan of poetry. But within the child-sized handful of poets whose works I enjoy, Dr. Seuss tops the list. Coming in close second is Dale Pendell. And so it was that—a couple of years ago—I shared the tale of dame Seuss's faux pas with Dale. I wanted to let him know how much I had appreciated his poetry over the past couple of decades, a point made all-the-more heartfelt by emphasizing the extremely fine (and discriminatingly small) company that I considered him to keep. Along with the works of Seuss, Dale's poems had redeemed an entire category of literature for me.

|

Prohibitionist propaganda had dominated drug data discourse and distribution during the 1980s. As the 1990s began, however, a few intrepid authors—some via their own independent desktop publishing efforts—provided the crucial kick-starts that helped ignite the engine of the Entheogenic Reformation.

Instant classics from this period include Sasha and Ann Shulgin's PIHKAL (1991) and TIHKAL (1997), Terence McKenna's The Archaic Revival (1991) and Food of the Gods (1992), Jim DeKorne's The Entheogen Review (1992) and Psychedelic Shamanism (1994), Jonathan Ott's Pharmacotheon (1993/1996), and Dale Pendell's Pharmako/Poeia (1995). These publications shared a common thread: each detailed scientific research that could be considered to have been prohibited by the government. Primarily occurring underground, the "Large Animal Bioassays" reported on in these texts were conducted by the publications' authors, their colleagues, and assorted anonymous or pseudonymous amateurs—kitchen chemists and basement shamans bold enough to experiment on their own bodies in pursuit of greater knowledge, and brave enough to share what they learned with others, while navigating a dangerous legal landscape that valued control culture over liberty and basic human rights. As McKenna aptly noted of the times, "...Western tradition has a built-in bias against self-experimentation with hallucinogens. One of the consequences of this is that not enough has been written about the phenomenology of personal experiences with the visionary hallucinogens."1

Dale embodied the D.I.Y. ethic. He was a scientist. A software developer. A singer of song. An artist, activist, peacenik, and an Anarchist. An ethnobotanist, an herbalist, a crafter of elixirs and tonics, extractions and distillations.

At Burning Man, the site of many first flesh meets, I spotted Dale sitting cross-legged under a PVC dome. On top of a cloth spread out in front of him, he was arranging a stack of leaves, a small pot of white powder, some other containers filled with various botanicals, and a few handfuls of what looked like over-round walnuts. He wielded what appeared to be an oddly designed metal nutcracker; extending down for a couple of inches from the fulcrum on the inside of the handles it had a slicing blade. I watched Dale struggle somewhat to push the blade repeatedly through one of the orbs, reducing it to thin slices. Realizing that I'd been staring, I asked: "Whatcha got there?"

|

"This is the traditional tool used to prepare these," he informed me through grunts of exertion, "but they are substantially softer and easier to slice when they're greener and not so dried out." He placed some of the slices onto one of the leaves, and added a few pinches of flavor-enhancing herbs topped off with some of the white power, which turned out to be either lime or baking soda (I can't recall). Despite having read that betel nut is one of the most popular stimulants worldwide, I had never previously come across it. Dale seemed to have a knack for obtaining obscure psychoactive plants.

Dale was a wild man. Dale was a gentleman. On first encountering his electrified caterpillar eyebrows, one might wonder if he was in league with the Devil. Such concerns vanished upon spotting the ever-present twinkle in his eyes, which instantly spilled the beans... they were, in fact, the Devil's eyebrows. Dale had pinched them on a dare while the great beast was napping. It wasn't as reckless as you might think. Dale understood that he'd have to poison a well from time to time.

Dale was a green man, a plant man, a gardener. A back-to-nature man. A leave-no-trace man. A tree hugger. And a carpenter. A builder of fires. He embodied the D.I.Y. ethic. He was a scientist. A software developer. A singer of song. An artist, activist, peacenik, and an Anarchist. An ethnobotanist, an herbalist, a crafter of elixirs and tonics, extractions and distillations. He made small batches, on his own Green Fairy label Pharmako Botanikos, of the finest wormwood-based elixir, which he generously shared with friends. His firewater conveyed an herbaceous bitterness unlike anything else; it truly had to be experienced to be appreciated.

He loved literature and was probably the most well-read individual I've had the pleasure of knowing. Shooting the shit with Dale provided access to an endless supply of intriguing information and entertaining escapades. It was a bit like having a conversation with the eponymous character from My Dinner with Andre, although Dale was much more mellow. His spoken and written words had a profound effect on my life, and the lives of numerous others.

|

I've continued my studies into Salvia divinorum, except that sometimes I think that it is the S. divinorum that is investigating me. I can say that it is the plants that have consciousness—that are the source of consciousness, and that animals got consciousness from eating plants—say that and not really be metaphorical. It astounds me.By June of 1993, he was distributing a fundraising letter attempting to obtain a grant to bolster his research efforts.1 It was a noble but short-lived effort. Several colleagues were intensely researching the plant around this same time. Before the month was over, Daniel Siebert had reported his findings on the human pharmacology of isolated salvinorin A, submitting a paper to the Journal of Ethnopharmacology in early August.

Siebert's paper confirmed Dale's speculation: the plant's primary psychoactive component was incredibly potent. Leading researchers in the field contemplated what sort of proactive action might be taken to reduce the chance that the plant and/or its active compound would fall victim to prohibitive legal restrictions. Consensus was that authors writing texts on the topic should focus on effective ways that people might use the whole plant or simple/crude extractions, instead of fostering the use, production, or distribution of salvinorin A in its pure form as a crystalline white powder. Dale did just that within the Salvia section of Pharmako/Poiea.

He encouraged newbie Salvianauts to begin their relationship with Ska Pastora by first cultivating and harvesting the plant; fresh leaves could be administered buccally as a quid, while plain dried leaf could be smoked in a pipe. After discouraging his readers from choosing the "crystal highway" as their path for this poison, he went on to describe a crude alcohol-based extraction process for yielding a "4X" material, formulated at this level so that it was possible for individuals without access to a milligram scale to safely "eyeball" a dose.

Since that chapter was published, knowledge of Salvia has increased worldwide and the plant has seen a substantial rise in the number of people who have tried it once or who take it occasionally. This heightened awareness may be partially attributable to the bizarre pop culture phenomenon of Salvia trip videos to YouTube, which neither Dale nor anyone else could have predicted. Within the realm of literature, on the other hand, Pendell's Pharmaco/Poeia has become established as a primary topical reference, commonly quoted from or cited in articles and books focused on Salvia divinorum.

Pendell was able to creatively employ a "plant's eye" viewpoint—whether it acted as a muse or a foil—in order to foster a dialogue with the sort of unusual inner voices that one hears at times during altered head spaces. Concern over whether or not the existence of "plant spirits" (or other associated "discarnate entities" that similarly cluster around the edges of altered consciousness) could ever be empirically proven to be "real" became less compelling. Things like increased access to artistic expression, improved introspective self-awareness, and an enhanced ability for viewing any situation from novel and unfamiliar perspectives that inspired increased empathy now seemed more important. His inclusion of conversations with plant spirits allowed him to evoke a more accurate representation of the psychic terrain traversed by increasing the color of language through poetic abstraction.

Dale was more than a gifted poet. His well-rounded works of prose beautifully balanced visionary insight, wry humor, scholarly detail, arcane references, practical wisdom, descriptive asides, important questions, and an impressive clarity of expression. His dedication to fundamental traditions of text was exemplified in his effort to compile and self-publish a separate bookletted Index for Pharmaco/Poeia, when the publisher failed to include one within the book itself.

A couple of times, I was charged with the responsibility to edit articles of Dale's published in The Entheogen Review and Erowid Extracts. It was easy work. Out of all of the texts I've edited over the years, Dale's required the least corrections and garnered the fewest suggestions for alterations. His writing blended style and substance with a page-turning force that was unquestionably all his own.

In 2014, a diagnosis of liver cancer caused Dale to sound a clarion call in search of a prospective donor for a liver transplant. A generous individual kindly volunteered, and the surgery occurred in March of 2015. At a gathering a year later, his friends felt overwhelming gratitude to the liver donor, who was present, for the gift he'd given to Dale and to all of us, by buying Dale some more time.

Dale continued to write for as long as he could. Near the end, when he was no longer able, he remarked: "The pain outran the pen."

True enough. Yet even so, in the big picture, I think that Dale's pen was mightier. For without a doubt, Dale will be remembered as someone who helped to make the world a more literate—and poetic—place.

References #

- McKenna T. The Archaic Revival. Harper Collins. 1991, p. 3.

- Pendell D. [as D.P.] "Network Feedback: Salvia divinorum and Plant Teachers". The Entheogen Review. 1992;1(2):10.

Notes #

- Within his "Proposal to Isolate and Study Salvinorin-A and Salvinorin-B, Reported to be the Active Ingredients of Salvia divinorum, 'Diviner's Sage'," Dale wrote that:

[...] much of the currently accepted information about Diviner's Sage is incorrect. In particular, it was believed that the active ingredient was unstable, that it could not be smoked, that only fresh material was active, and that the effects of the plant were "mild". All of these assumptions, by the author's findings, are incorrect. The author has found activity in dried material several years old, and preliminary calculations reveal that the ingredients may be active at doses of less than one milligram—fully an order of magnitude more powerful than the better known smokable hallucinogen, N,N,dimethyltryptamine (DMT).