|

|

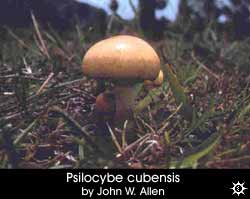

INTRODUCTION Mind-altering (psilocybine containing) mushrooms have been traditionally used in religious healing and curing ceremonies by native peoples in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years. Today, the recreational use of hallucinogenic fungi by Westerners is widespread, especially in various regions of the United States, Canada, Mexico, Caribbean, Great Britain, Europe (especially in the Netherlands), Scandinavia, South America, Southeast Asia, India, Bali, Samoa; Australia and New Zealand. The modern, non-traditional use of hallucinogenic mushrooms has been stimulated, by media reports in newspapers, magazines, word-of-mouth communication, the World Wide Web and Internet, and also by the scholarly and popular journal publications of the renown ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson, (Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary, author and traveler Jeremy Sanford, health guru Andrew Weil, and others (see Allen , Merlin & Jansen, 1991). This field guide reviews the history of both the accidental and purposeful use of psychoactive mushrooms in Australia and New Zealand. Information in this guide has been gathered from personal experiences in Australia by the author and from reports in the scientific literature, news items appearing in the popular press, and personal communications with Australian and New Zealand (NZ) professionals (Unsigned 1970; O'Neill, 1986). Furthermore, descriptions of both the physical and mental effects resulting from both the accidental and deliberate ingestion of some species of psychoactive mushrooms in Australia and New Zealand during the past 50 years is discussed.  There are more than 1 dozen species of "magic mushrooms" in Australia and New Zealand. Four of these species are dung (manure) inhabiting mushrooms. They include Psilocybe cubensis and/or Psilocybe subcubensis (known locally as "gold caps" and/or "gold tops"), Psilocybe subaeruginosa, and Copelandia cyanescens (the latter is known locally as "blue meanies"). These four species contain the mind altering alkaloids psilocybine and psilocine and are the most common hallucinogenic mushrooms in Australia. In New Zealand, the most commonly used species are Copelandia cyanescens and Psilocybe semilanceata, the latter species is recognized throughout the world as the "liberty cap"). This species only occurs in manured soil and does not grow directly from the dung of cattle, sheep or other four legged farm animals. Psilocybe cubensis the most popular of these species, is well known throughout much of the world; however, this species is not known to occur in New Zealand.

There are more than 1 dozen species of "magic mushrooms" in Australia and New Zealand. Four of these species are dung (manure) inhabiting mushrooms. They include Psilocybe cubensis and/or Psilocybe subcubensis (known locally as "gold caps" and/or "gold tops"), Psilocybe subaeruginosa, and Copelandia cyanescens (the latter is known locally as "blue meanies"). These four species contain the mind altering alkaloids psilocybine and psilocine and are the most common hallucinogenic mushrooms in Australia. In New Zealand, the most commonly used species are Copelandia cyanescens and Psilocybe semilanceata, the latter species is recognized throughout the world as the "liberty cap"). This species only occurs in manured soil and does not grow directly from the dung of cattle, sheep or other four legged farm animals. Psilocybe cubensis the most popular of these species, is well known throughout much of the world; however, this species is not known to occur in New Zealand.Other species described in this guide are known to occur in manured soil, in pastures, meadows, grazing lands, some lawns and in the bark mulch and woodchips of deciduous woods. CATTLE AS A POSSIBLE DISPERSAL MECHANISM FOR PSYCHOACTIVE DUNG FUNGI One may ask the question, "how did these mushrooms arrive in Australia and New Zealand?" Well some species may be endemic, that is, they were already there naturally. Other species such as the above described dung-inhabiting mushrooms most likely appeared after the introduction of cattle on the subcontinent.  The first livestock to arrive in Australia were brought from the Cape of Good Hope in 1788, and included 2 bulls and 5 cows, along with other domesticated farm animals. By l803, the government owned approximately 1800 cattle, most of which were imported from the Cape, Calcutta, and the west coast of America. It was during this period that some of the visionary mushrooms mentioned in this field guide probably first appeared in Australia (Unsigned, 1973). According to Australian mycologist John Burton Cleland (1934), "fungi growing in cow or horse-dung and confined to such habitats, must in the case of Australia, all belong to introduced species". It is believed to have been the South African dung beetle which may have actually spread the spores. According to English mycologist Roy Watling of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Glasgow, Scotland, "it must be remembered that fungi can change substrate preferences and there are coprophilous fungi on kangaroo droppings etc." Some mycologists who have studied the "magic mushrooms" in Australia and NZ claim that the "use of P. cubensis as a recreational drug tends to confirm the belief that [some] farmers in early times [may have] added one or two basidiomes [gilled mushrooms] to a meal to liven it up [and still do] Margot & Watling, 1981)."

The first livestock to arrive in Australia were brought from the Cape of Good Hope in 1788, and included 2 bulls and 5 cows, along with other domesticated farm animals. By l803, the government owned approximately 1800 cattle, most of which were imported from the Cape, Calcutta, and the west coast of America. It was during this period that some of the visionary mushrooms mentioned in this field guide probably first appeared in Australia (Unsigned, 1973). According to Australian mycologist John Burton Cleland (1934), "fungi growing in cow or horse-dung and confined to such habitats, must in the case of Australia, all belong to introduced species". It is believed to have been the South African dung beetle which may have actually spread the spores. According to English mycologist Roy Watling of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Glasgow, Scotland, "it must be remembered that fungi can change substrate preferences and there are coprophilous fungi on kangaroo droppings etc." Some mycologists who have studied the "magic mushrooms" in Australia and NZ claim that the "use of P. cubensis as a recreational drug tends to confirm the belief that [some] farmers in early times [may have] added one or two basidiomes [gilled mushrooms] to a meal to liven it up [and still do] Margot & Watling, 1981)."  More than half of Australia's beef cattle can be found in the coastal areas of Queensland and New South Wales; and the 20 to 30 inch (500-750mm) rainfall belt of Queensland, New South Wales and Northern Victoria, generally provide adequate climatic environments for the growth of psilocybian mushrooms, especially after heavy rains. It has been suggested that "Psilocybe cubensis was introduced into Australia accidentally by early settlers along with their livestock." This same spore dispersal mechanism also probably applies to Copelandia cyanescens, Panaeolus subbalteatus and several additional species known to occur in or around the dung of other ruminants. This includes Psilocybe semilanceata and the non-hallucinogenic "haymaker's" mushroom Panaeolina foenisecii.

More than half of Australia's beef cattle can be found in the coastal areas of Queensland and New South Wales; and the 20 to 30 inch (500-750mm) rainfall belt of Queensland, New South Wales and Northern Victoria, generally provide adequate climatic environments for the growth of psilocybian mushrooms, especially after heavy rains. It has been suggested that "Psilocybe cubensis was introduced into Australia accidentally by early settlers along with their livestock." This same spore dispersal mechanism also probably applies to Copelandia cyanescens, Panaeolus subbalteatus and several additional species known to occur in or around the dung of other ruminants. This includes Psilocybe semilanceata and the non-hallucinogenic "haymaker's" mushroom Panaeolina foenisecii. While cattle are raised in all Australian states, as well as in the central lowlands, recreational users have been known to export these psychoptic species to various areas in Australia from areas where they were collected. In the case of New Zealand, hereafter referred to as NZ, cattle are the primary source for Copelandia cyanescens, but the "liberty cap" mushroom Psilocybe semilanceata only grows in the manured soil of four-legged ruminants and not directly from manure (Jansen, Pers. Comm., 1988). The identification section of this guide documents reported locations for more than 1 dozen species of psilocybian mushrooms in Australia and NZ which most likely have been used at one time or another for recreational purposes. COMMON EPITHETS  Most users of the psychoactive visionary mushrooms have very little knowledge of their scientific names. Instead, they have given their favorite species local epithets which are commonly used by those who collect and ingest them. Some of these popular names are also known and applied by users outside of Australia and NZ.

Most users of the psychoactive visionary mushrooms have very little knowledge of their scientific names. Instead, they have given their favorite species local epithets which are commonly used by those who collect and ingest them. Some of these popular names are also known and applied by users outside of Australia and NZ."Magic Mushrooms" is the most common term applied to any mushroom which contains psilocybine and/or psilocine. It was invented by a Life Magazine editor in l957 ( see Wasson, l957). Psilocybe cubensis is known in Australia as "golden tops", "gold tops" or sometimes "gold caps." The Australian epithets may have been given to this species by members of a local, drug-using group of surfers which frequented the Gold Coast region of Eastern Australia; however, some of these names have apparently been used to describe several different species of Psilocybe by users in Australia (see Allen, 1997). As mentioned above, Psilocybe cubensis is not known to occur in New Zealand.  Those who ingest Copelandia cyanescens, known in Australia and New Zealand as "blue meanies", also refer to this species as "Blue Legs", "golden tops" or "gold caps". The latter two nicknames, as well as "dimple tops" and "cone heads", are common terms applied to Copelandia cyanescens in the Hawaiian Islands; and some of these same popular names have also been used by visiting surfers from both New Zealand and Australia, to describe the macroscopic characteristics of Copelandia cyanescens. These same surfers visiting Hawaii's North Shore have reportedly ingested mushrooms prior to surfing, as do many of the locally based surfers in Australia and NZ.

Those who ingest Copelandia cyanescens, known in Australia and New Zealand as "blue meanies", also refer to this species as "Blue Legs", "golden tops" or "gold caps". The latter two nicknames, as well as "dimple tops" and "cone heads", are common terms applied to Copelandia cyanescens in the Hawaiian Islands; and some of these same popular names have also been used by visiting surfers from both New Zealand and Australia, to describe the macroscopic characteristics of Copelandia cyanescens. These same surfers visiting Hawaii's North Shore have reportedly ingested mushrooms prior to surfing, as do many of the locally based surfers in Australia and NZ.The epithet "blue meanies" refers to 1) the relative potency of the species and the intense blue oxidation (indicating the presence of psilocine) caused by damage to the cap and/or stem when the mushroom has been bruised by human handling, and 2) `blue meanies' is connected with the Beatles film `Yellow Submarine'. "gold tops" or "golden caps" often refer to the color of the pileus of both P. cubensis and C. cyanescens, which are hygrophanous (changing color when drying). In the United States, Canada, Great Britain and Europe, Psilocybe semilanceata is often referred to as the "liberty cap" (see Allen 1997a and 1997b) and is also known to many Europeans as "Psilos.". In New Zealand, the term `magic mushroom' is certainly more popular than any other term used in identifying psilocybian mushrooms. PUBLIC AWARENESS OF PSILOCYBIAN FUNGI It has been suggested by an Australian physician that the general public in Australia, as well as members of its drug using subculture, first became aware of the visionary properties of these psychoactive mushrooms by a visiting surfer(s), who came from either New Zealand or the United States (Hawaii) and most likely provided ethnomycological information to local surfers (McCarthy, 1971). This physician reported that the use of psychoactive mushrooms, as well as 21 other drugs "was well demonstrated during a survey on drug abuse that was conducted in Southern Queensland during l969." This survey relied on interviews of 51 people belonging to "the `surfer' subculture local beach resorts". In this report, the doctor believed that "although the survey involved surfers and their female friends, there is no suggestion that the use of these drugs is confined to this group, which constitutes but a proportion of our (Australian) young drug taking community." It is thus likely that word-of-mouth communication made a significant contribution to the increasing use of "magic mushrooms" in Australia and NZ. In addition, many early users of "magic mushrooms" in Australia may have first become aware of their mind-altering and visionary effects by reading the published literature or the many news items appearing in the popular Australian press during the late l960's and early l970's. These news items often described both accidental and deliberate intoxication's which resulted from the ingestion of several varieties of "magic mushrooms". For example, in 1972, one local newspaper report provided an account regarding the use of these mushrooms by young teenagers at a local high school in Brisbane: "...children at a suburban school are getting high on mushrooms called 'Gold Tops.' The mushrooms are common along the Brisbane River near Toowing High School, and children in search of `kicks' have been experimenting with them (Unsigned, 1972)." It would be very obvious to anyone who read this above mentioned news item, when it appeared in print, that those searching for hallucinogenic mushrooms would be able to find them if they so desired. There is yet another factor that may have played a significant role in promoting interest in the use of psychoactive mushrooms in Australia and NZ. Some drug users or mycophillic individuals may have read or heard of R. Gordon Wasson's personal account of his adventurous rediscovery of an hallucinogenic mushroom cult among the Mazatec Indians of Southern Mexico. Dr. Wasson reported the ceremonial use of certain mushrooms as divinatory substances among the Mazatecs and other native peoples in Oaxaca, Mexico (see Wasson, 1957). This journalistic report of Wasson's research expedition appeared in an international edition of Life Magazine in the late l950's, providing many drug users and others with the incentive to seek out, find, and eventually experiment with these mushrooms. The media has also played an indirect, unintentional role. For example, in the Pacific Northwest United States, local radio stations, and newspapers, often inform their listening and viewing public on the annual arrival of mushroom season; even mentioning the fruiting of psilocybian mushroom throughout several locations in the Pacific Northwest United States. Additionally, as noted above, with the passing of the 1990's, word of the mushroom can now reach millions of viewers through the World Wide Web and the Internet. PSYCHOACTIVE POTENCY OF AGARIC SPECIES The majority of adverse physical effects or negative psychological reactions produced by "magic mushrooms" generally result from inappropriate set and expectation, or because of improper dosage, which may vary considerably among consumers, different mushroom species, or even within an individual species. The question of dosage is often confused by the variation in the source of the hallucinogenic mushroom species which is consumed. For example, Psilocybe cubensis, when picked and eaten from its natural dung (manure) habitat, produces a relatively mild mind-altering experience, which is evident from the large amounts of fresh specimens needed to achieve a threshold experience. However when grown in vitro (indoor laboratory cultivation and/or illicit cultivation), Psilocybe cubensis apparently can produce a more potent strain capable of inducing a very intense visual, sometimes quite disturbing, experience. This dosage assumes that the consumption of 1 to 3 gm of dried material would be too low if the mushroom specimen came from a wild source. This low potency for Psilocybe cubensis has been confirmed by research scientists Margot & Watling, (1981), who were surprised by the comparatively small amounts of psilocybin and psilocin which they extracted from wild specimens collected from five different locations in Australia. This suggests that a much larger dose would be required to produce significant hallucinations. It is possible that the chemicals most likely degenerated between the time that they were harvested and the time of analysis. However, it should be noted that a strain of Psilocybe cubensis producing different flushes (harvests) will vary somewhat in potency between flushes. DOSAGE LEVELS  Most recreational users of Psilocybe cubensis (when grown in vitro) require a dosage of 1 to 2 gm of dried mushrooms to produce an altered state of consciousness; a clinical dosage for Psilocybe cubensis, on the other hand, had previously been reported as ranging from 3 to 5 gm of dried material. This dosage would be comparable to the amount of fungal material consumed for religious purposes in a Mazatec Indian healing and curing ceremony. In 1982, one research team "found that the level of psilocybin and psilocin varies over a factor of 4 among various in vitro cultures of Psilocybe cubensis, while specimens from outdoors varied tenfold." A fresh dosage of Psilocybe cubensis in Australia would be approximately from 1 to 2 large mushrooms weighing up to as much as one fresh ounce, or as many as from 25 to 50 small mushrooms equaling the same weight amount. Ethnopharmacologist Jonathan Ott (1976, 1993) noted that he has observed "the ingestion of from 0.5 gm to 5.9 gm dried weight (10 gm to 40 gm fresh)", of various species of Psilocybe. Dosage for Psilocybe subcubensis would be the same as for Psilocybe cubensis. Both of these latter two species are macroscopically alike.

Most recreational users of Psilocybe cubensis (when grown in vitro) require a dosage of 1 to 2 gm of dried mushrooms to produce an altered state of consciousness; a clinical dosage for Psilocybe cubensis, on the other hand, had previously been reported as ranging from 3 to 5 gm of dried material. This dosage would be comparable to the amount of fungal material consumed for religious purposes in a Mazatec Indian healing and curing ceremony. In 1982, one research team "found that the level of psilocybin and psilocin varies over a factor of 4 among various in vitro cultures of Psilocybe cubensis, while specimens from outdoors varied tenfold." A fresh dosage of Psilocybe cubensis in Australia would be approximately from 1 to 2 large mushrooms weighing up to as much as one fresh ounce, or as many as from 25 to 50 small mushrooms equaling the same weight amount. Ethnopharmacologist Jonathan Ott (1976, 1993) noted that he has observed "the ingestion of from 0.5 gm to 5.9 gm dried weight (10 gm to 40 gm fresh)", of various species of Psilocybe. Dosage for Psilocybe subcubensis would be the same as for Psilocybe cubensis. Both of these latter two species are macroscopically alike. The usual dosage for Copelandia cyanescens required to induce psychedelic visual effects ranges from 1 to 3 large specimens (cap diameter c. 5 mm), or as many as 5 to l0 medium-sized mushrooms (cap diameter c. 2.5 mm); however, personal tolerance to this species may occur with continued use, and some who consume large amounts of this mushroom have reportedly ingested as many as 50 to 200 fresh specimens of various sizes. Dosage for Psilocybe subaeruginosa is approximately the same as that given for Psilocybe cubensis, 1 to 3 large specimens, 4 to 6 small specimens, or 1 to 2 gm dried material. Panaeolus subbalteatus requires at least 28 gm fresh (l0 to 20 or more mushrooms), or as many as 2 to 5 gm dried material. Dosage for Psilocybe semilanceata is reported at 7 gm to 10 gm fresh (approximately 20 to 30 mushrooms), or 1 gram dried. DOSAGE FOR WOOD CHIP SPECIES  Gymnopilus spectabilis, now considered a synonym of Gymnopilus junonius requires a dosage of 4 to 8 fresh ounces (112-224 gm fresh). According to mycologist Roy Watling, the Australian `form' is probably Subs. pampeanus. However, this mushroom is very bitter and it is most likely not consumed in Australia for recreational use.

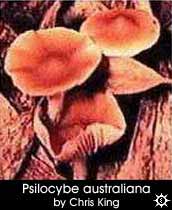

Gymnopilus spectabilis, now considered a synonym of Gymnopilus junonius requires a dosage of 4 to 8 fresh ounces (112-224 gm fresh). According to mycologist Roy Watling, the Australian `form' is probably Subs. pampeanus. However, this mushroom is very bitter and it is most likely not consumed in Australia for recreational use. Dosages for Psilocybe australiana Guzmán & Watling, Psilocybe eucalypta Guzmán & Watling, Psilocybe kumaenorum Heim, Psilocybe tasmaniana Guzmán & Watling and Psilocybe makarorae Johnston & Buchanan are unknown at the present time. However, according to several people who have bioassayed some of these new species, reports indicate that they are just as potent as Psilocybe cyanescens (the most potent of species commonly found in the Pacific Northwest United States; British Colombia, Canada; Great Britain and Europe) and the suspected hallucinogenic properties of Panaeolina foenisecii (a common lawn mushroom sometimes considered as hallucinogenic) remain doubtful, as does the appearance of Psilocybe collybioides in Australia.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|