|

|

ACCIDENTAL INGESTIONS DOWN UNDER  The earliest published report of an intoxication from a suspected psilocybian mushroom in Australia occurred sometime prior to 1934. In 1934, Dr. John Burton Cleland, M.D., wrote that "......Some kind of toadstools give rise to a kind of intoxication. A former colleague of mine told me how his parents ate once a dish of mushrooms, and, as the meal progressed, they gradually became more and more hilarious, the most simple remarks giving rise to peals of laughter. The intoxication passed off without any further unpleasant effects." Cleland further noted that the mushrooms ingested were most likely a dung inhabiting species; probably Panaeolus.

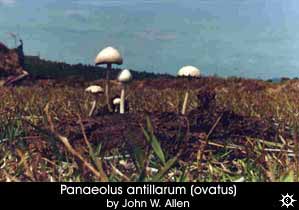

The earliest published report of an intoxication from a suspected psilocybian mushroom in Australia occurred sometime prior to 1934. In 1934, Dr. John Burton Cleland, M.D., wrote that "......Some kind of toadstools give rise to a kind of intoxication. A former colleague of mine told me how his parents ate once a dish of mushrooms, and, as the meal progressed, they gradually became more and more hilarious, the most simple remarks giving rise to peals of laughter. The intoxication passed off without any further unpleasant effects." Cleland further noted that the mushrooms ingested were most likely a dung inhabiting species; probably Panaeolus.Between 1941 and 1945, numerous reports in the Australian journals regarding the poisoning by what mycologists believed were Panaeolus ovatus (the suspected "hysteria fungus") mushrooms. Since this species is not psychoactive, one must assume that the mushrooms in question were Copelandia cyanescens (Unsigned, 1941; Trotter, 1944). After 1945, no cases involving the accidental ingestion of inebriating mushrooms were reported in the Australian medical journals or the press until 1957. In that year the Wassons had announced their discovery of the ceremonial use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico.  James H. Willis, in his 1957 book "Victorian Toadstools and Mushrooms" published this interesting anecdote regarding the numerous reports in the scientific literature which described poisonings attributed to the suspected ingestion of Panaeolus ovatus: "...Rumour has it that they will cause an intoxication under which the victim suffers a strange sensation of growing taller and over-topping the objects about him: Who knows but this may (very well) be the magic mushroom of `Alice In Wonderland' fame." Willis then goes on to say that, "P. ovatus has intoxicated people near Sydney." Remember that P. ovatus is not psychoactive and these mushroom poisonings were probably caused by the consumption of various Copelandia mushroom species; probably Copelandia cyanescens.

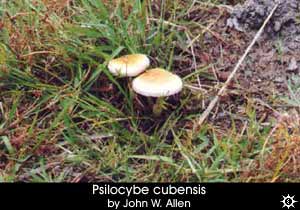

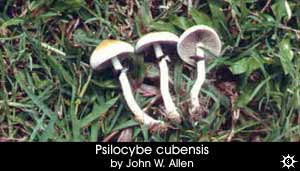

James H. Willis, in his 1957 book "Victorian Toadstools and Mushrooms" published this interesting anecdote regarding the numerous reports in the scientific literature which described poisonings attributed to the suspected ingestion of Panaeolus ovatus: "...Rumour has it that they will cause an intoxication under which the victim suffers a strange sensation of growing taller and over-topping the objects about him: Who knows but this may (very well) be the magic mushroom of `Alice In Wonderland' fame." Willis then goes on to say that, "P. ovatus has intoxicated people near Sydney." Remember that P. ovatus is not psychoactive and these mushroom poisonings were probably caused by the consumption of various Copelandia mushroom species; probably Copelandia cyanescens.According to the physician Dr. A. E. Stocks (1963), between 1957 to 1963, 11 patients were admitted into the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane due to complications of poisoning from several different species of toxic and/or mind-altering fungi. Five of these cases were definitely caused by psilocybian mushrooms (Psilocybe cubensis); and two other patients, whose onset of disturbing symptoms began after ten minutes of consumption of the mushrooms, were also probably affected by psilocybian intoxication. Stocks failed to mention whether these mushroom intoxications were accidental or deliberate ingestions, and he inadvertently reported that R. Gordon Wasson's personal first experience with these mushrooms had produced undesirable effects. Although Wasson's first experience had been reported as being profound and ecstatic, it is possible that Stocks was actually referring to Swiss chemists Albert Hofmann's personal account regarding his somewhat unpleasant initial experience while under the influence of Psilocybe mexicana (Hofmann, 1980) or Dr. Sam Stein of The University of Chicago's frightening experience while under the influence of 5 dried gm of in vitro grown specimens of Psilocybe cubensis (Stein, 1958). Although Dr. Stocks suggested that the hallucinogenic effects of these mushrooms were more potent than either lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or mescaline (Peyote), it should be pointed out that many users of these drugs prefer the natural experience of the mushrooms since this has a shorter duration of 3 to 6 hours as opposed to the 8 to 12 hour experience of LSD, mescaline or MDA. Stocks's paper on mushroom poisoning presents us with two case histories of psilocybian intoxication. The first referred to a female who: "...noted after 30 minutes of ingestion, a dark cloud passing across her eyes, then a green cloud. Her tongue felt thick and she complained of being paralyzed. There was no impairment of memory, and no hallucinations other than the colored vision; the symptoms resolved in 12 hours. This patient described her experience as distinctly unpleasant." The second case Stocks described involved a male who sought medical treatment at another southeast Queensland hospital. "...After 5 minutes of ingestion, the patient reported that he felt a tingling in both of his temples, and a general feeling of strangeness. His T.V. set `changed color' and the images on the screen became brighter and steel-blue. Vision later became blurred, and objects seemed either too large or too small, and appeared alternately to advance and recede from him. Later, sharp images of dragons appeared in a brilliantly-colored oriental setting. He had to fight to stay awake, experienced by a dry mouth and a tongue `like leather' ,and regards the whole experience as definitely unpleasant." On June 3, 1969, at 7 P.M., the Australian Broadcasting Commission, aired the following story of an intoxication which occurred near Forster along the Central Coast of New South Wales. "The New South Wales Department of Agriculture is investigating the case of a Sydney couple who had violent hallucinations after eating mushrooms which they had picked during a weekend sojourn. The couple, both professional artists, were kept under observation at the Forster Hospital, while the effects from the mushrooms wore off. For over three hours, they experienced symptoms similar to an LSD intoxication. The couple told attending physicians that they had each eaten about a dozen bush mushrooms, and within five minutes or more were experiencing hallucinations. The woman reported that she felt as if her skin was peeling off of her hands, and she believed that she was dying. They were both terrified from their inebriation. Samples of the mushrooms were sent to the Department of Agriculture to be analyzed for identification" (Southcott l974). In this case, as well as many others involving use of suspected hallucinogenic fungi, very rarely is reference made as to whether or not the specimens of mushroom material, received by the toxicologists or mycologists is fresh, dried, or derived from a gastric lavage.  In 1971, a noted physician wrote that "Over the years, the Southport Hospital on the Gold Coast has had a steady flow of accidental poisonings with Psilocybe cubensis McCarthy, 1971). A good example occurred in 1969 when a whole family was affected after a picnic somewhere in the mountains." No mention is made as to the exact location where this incident took place. Symptoms from this intoxication included "...Euphoria, depression, inappropriate speech and answers, visual hallucinations, ataxia, vomiting, urinary incontinence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and dilated pupils, and a respectable family man was caused to run naked through the hospital, trying to molest the nurses who were attempting to treat his illness".

In 1971, a noted physician wrote that "Over the years, the Southport Hospital on the Gold Coast has had a steady flow of accidental poisonings with Psilocybe cubensis McCarthy, 1971). A good example occurred in 1969 when a whole family was affected after a picnic somewhere in the mountains." No mention is made as to the exact location where this incident took place. Symptoms from this intoxication included "...Euphoria, depression, inappropriate speech and answers, visual hallucinations, ataxia, vomiting, urinary incontinence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and dilated pupils, and a respectable family man was caused to run naked through the hospital, trying to molest the nurses who were attempting to treat his illness". Another case of mushroom poisoning occurred in 1971 when a female drug user, aged 17, of Adelaide, who had a history of marijuana use, and on one previous occasion had used LSD, sought medical treatment after having a `bad trip' while under the influence of Copelandia cyanescens, which was obtained in the vicinity of Adelaide. She soon became frightened, seeking immediate medical attention, because she thought that she was a banana, and that somebody was attempting to skin her (Southcott, 1974). Following is an excerpt from a news item appearing in a local Australian paper... "A small brown mushroom that grows widely in the Adelaide Hills in July and August is providing drug addicts and thrill seekers with a potent hallucinogenic drug. The mushrooms, brown all over, contains the drug Psilocybine, which is prohibited by the Narcotics and Psychotropic Drugs Act (of South Australia). The mushroom is being passed around in fresh and dried forms. Three young people who tried the mushroom drug last year were admitted into the Royal Adelaide Hospital and treated for poisoning (Hailstone, 1972)." An expert [no mention is presented as to who the expert is], at the Waite Agricultural Research Institute warned that even small quantities of it [psilocybine containing mushrooms] could cause serious poisoning, however, Lloyd Davis, Pharmacological Inspector for the South Australia Health Department said that "Users and those interested knew what the mushrooms looked like, where they could be found, and how to use them." Davis also "Doubted whether amateurs experimenting with them would be poisoned because there was a well organized system of communication among users and would be users". Another interesting reported case of alleged mushroom poisoning concerns a young girl in Campbelltown, a suburb of Adelaide. Clinical records from the Adelaide Children's Hospital describe this 3 year old child as being a lively spirited red-head, with an on going allergic condition. Her mental distress symptoms discussed below, may have resulted from the fact that she indulged in pica (one who eats dirt, grass, leaves and twigs). However, Dr. Ronald V. Southcott of South Australia reported that: Beginning in 1972 that "for some months she had been known to have repeated episodes of hallucinations, and each attack was marked by her person being cold and clammy, with frequent bed urination including bedwetting. Her attacks would usually commence about six to eight hours after being allowed to play outdoors around her home, in the lawns and the garden." In fact, according to the mother, during the past 12 months her daughter had at least a dozen such attacks, which were very frightening and distressing to the child. Symptoms reported by this little girl included: seeing colored lights on the ceiling, seeing cats that were not there, and feeling that she was bigger than she really was. An attack usually lasted no more than four hours. The first attack occurred when the child was not more than two years eight months old.  Specimens of the fungus were then obtained and photographed, both before and after drying. Dr. Ronald Southcott photographed the fungi in situ among the grass. In l974, "Dr. Roy Watling of the Royal Botanic Gardens of Edinburgh, Scotland, visited Adelaide and identified the fungal specimens as being species of Panaeolus foenisecii.

Specimens of the fungus were then obtained and photographed, both before and after drying. Dr. Ronald Southcott photographed the fungi in situ among the grass. In l974, "Dr. Roy Watling of the Royal Botanic Gardens of Edinburgh, Scotland, visited Adelaide and identified the fungal specimens as being species of Panaeolus foenisecii. While the evidence in this case involving this particular species is only circumstantial, it appears to be the only justifiable explanation in attributing the girl's symptoms" . While the symptoms and duration of affliction described in this particular incident are similar to those often attributed in the literature to psilocybin poisoning, it must be noted here that the onset of psilocybin intoxication normally occurs within 15-30 minutes after ingestion. This child's intoxications, however, always seemed to occur within 6 to 8 hours after she was allowed to play in her yard outdoors, or upon waking up after taking a nap. Besides the child's distressing habit of indulging in pica, Southcott had also noted that the child was experiencing some minor psychological difficulties with her mother. This may have contributed to the child's condition. However, based on the above observations, it is of the opinion of the author that the psychological symptoms exhibited by this child were not caused by the ingestion of Panaeolus foenisecii (for a more descriptive analysis of this incident and similar alleged poisonings by Panaeolus foenisecii, see Allen and Merlin, 1992). TREATMENT FOR PSILOCYBIAN MUSHROOM POISONING The major dangers associated with psilocybin poisonings are primarily psychological in nature. Anxiety or panic states ("bad trips"), depressive or paranoid reactions, mood changes, disorientation and an inability to distinguish between reality and fantasy may occur. Recommended treatment for this type of poisoning should always be primarily supportive. Mycologist Dr. Joseph Ammirati of the University of Washington and his colleagues claim that "no specific treatment can be recommended for psilocybin poisoning in humans". Other doctors have "stress[ed] the importance of measures to reduce absorption of the toxins involved". This involves either, e.g., gastric lavage or emesis Lincoff & Mitchell, 1977; Rumack & Saltzman, 1978; Smith, 1978).

In 1988, Dr. Jansen noted that cases which present medically fall into several groups:

Other doctors have also speculated that a lavage is not merited if psilocybian mushrooms have been positively identified as the source of discomfort. It has also been suggested that "gastric intubation can be difficult in these young patients who are often already distressed and not infrequently aggressive. Furthermore the mushrooms may block the standard lavage tubes [used] for drug overdoses." The inherent danger from the ingestion of wild mushrooms lies not so much in the consumption of an hallucinogenic variety, but rather in the picking and eating of a toxic species which might resemble an hallucinogenic variety. Dr. Gastón Guzmán (and his colleagues wrote that "field and laboratory studies strongly indicate that psychoactive mushroom use as it normally occurs does not constitute a drug abuse problem or a public health hazard" (Guzmán et al., 1976). In addition, a recent survey conducted among college students in California, suggests that "the low frequency and few negative effects of [hallucinogenic mushroom] use indicate that abuse does not present a social problem, nor is there evidence for predicting the development of a problem" Thompson et al., 1985). FLASHBACKS In 1973, Dr. Hall was the Principal Research Officer of the Narcotics Section of the Commonwealth Police Force in Canberra. Dr. Hall had also reported that several drug users had been experiencing recurring `flashbacks' from mushrooms that were similar to `flashbacks' which were associated with LSD consumption. According to Dr. Karl L. R. Jansen, there is not any firm evidence that mushroom `flashbacks' can occur. Researchers in 1983, have reported that out of 318 specific cases of Psilocybe intoxications occurring in England between l978-l981, 21 patients experienced `flashback phenomena of some form' for up to four months after ingestion", and also mentioned that some of these were the result of drug synergy and polydrug abuse. "...However, with such a controversial phenomena as `flashbacks', it is necessary to specify precisely what form these do take, so that they may be distinguished from psychological stress reactions wrongly attributed to past drug use." Dr. Hall also pointed out that "if solutions of mushroom extracts were injected intravenously, the results could be very serious." There are no known cases of such injections, and it seems extremely unlikely that anyone would attempt this. PSILOCYBIAN FUNGI AND THE LAW Between the years l969 and l975, the non-traditional use of psychoactive mushrooms does appear to have increased rapidly in Australia. During this period, heavy rains in the spring of 1969, produced bumper crops of Psilocybe cubensis, and large quantities of this species was consumed by hundreds of drug users, who ate them raw, with or on toast, or in soup. These youthful users who were members of Australia's counter culture described their effects from the ingestion of these mushrooms as being similar to LSD, but more natural. Government authorities soon claimed that the popularity of psychoactive mushrooms at this time [winter, l969], diminished due to many regular users who began to experience extreme depression and lethargy; some users even reported that they had `lost their will to live'. This resulted in a number of "freakouts", and by the end of l969, local authorities assumed that their popularity [use of mushrooms] had declined. On Friday, July 11, l969, four young men, aged 20-22 years, from New South Wales, were each fined $200.00, on charges of being in possession of the drug psilocybine. "A complaint was registered by the manager of `Sippy Downs' station near Nambour, which is about sixty miles north of Brisbane, stating that the young adults had gained illegal entry onto the owner's private property. Detective-constable T. Tame and another police officer went out to the property. There they found a parked gray van alongside the road. A box containing the mushrooms was observed by the officers on the floor of the van, so the police asked the four adults to accompany them to the Nambour Police Station, which the four men consented to do. The magistrate of the court found the young men guilty and allowed them two weeks to pay their fines. If the fines were not paid on time, then they would be found in default and would have to serve a sentence of one month imprisonment" (Unsigned. 1969). Cattle ranchers in Australia have often been referred to as irate that some mushroom pickers have little respect for their property, trespassing frequently in search of psychoactive fungi. In the United States mushroom pickers have been known to leave gates open so that the cattle wander out onto the roadways, litter the fields and paddocks with garbage such as bottles, beer cans, etc., break down fences and bring dogs into the pastures which chase the cattle.  By March of 1971, an export market was established by dealers and users, who had made Psilocybe cubensis available to users in Sydney and other larger cities throughout Australia. By 1972, Tasmanian authorities became concerned that the widespread collection and ingestion of psychoactive fungi in their state would attract interested people from the mainland (Australia) to Tasmania, who would come in search of these species. Additionally, Dr. Malcomb Hall stated in l973, that "exportation of fungi from Tasmania to the mainland is highly likely, as knowledge of suitable species becomes [more] widespread." Its growing popularity probably occurred because of the widespread attention given to this mind-altering activity. This included personal communication among friends, increased attention in the popular press, and articles written in scientific journals.

By March of 1971, an export market was established by dealers and users, who had made Psilocybe cubensis available to users in Sydney and other larger cities throughout Australia. By 1972, Tasmanian authorities became concerned that the widespread collection and ingestion of psychoactive fungi in their state would attract interested people from the mainland (Australia) to Tasmania, who would come in search of these species. Additionally, Dr. Malcomb Hall stated in l973, that "exportation of fungi from Tasmania to the mainland is highly likely, as knowledge of suitable species becomes [more] widespread." Its growing popularity probably occurred because of the widespread attention given to this mind-altering activity. This included personal communication among friends, increased attention in the popular press, and articles written in scientific journals. The written accounts referred to both the accidental and deliberate consumption of several species of mushrooms containing either psilocybin and/or psilocin. These articles and news items provided both the public and law enforcement agencies with information regarding the existence, use, and effects of these mushrooms throughout South Australia, New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, Northern Territory, Tasmania, and the Australian Capital Territory. However, usage of these psychoactive fungi became popular in New Zealand during the late l970's and in 1987, a government report mentioned that "LSD and hallucinogenic mushrooms were [now] being abused by eating in New Zealand, mainly by 15-19-year-olds." It should be noted that the growth of this illicit activity in Australia preceded the publication of several widely read, popular and scientific essays which described the recreational use of these hallucinogenic mushrooms in the United States during the middle and late l970's. Between the years l969-l971, the increasing use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in various areas of Australia during the late l960's and early l970's, attracted the attention of the Central Crime Intelligence Bureau of the Commonwealth Police Force, whose principal research officer showed concern about the increasing abuse of these fungi in his country. He stated that because of the availability of "free" hallucinogenic mushrooms, "few if any LSD sales were taking place in Hobart in l972." While each Australian state has enacted legislation controlling these psychoactive substances and their analogues, only one state, Queensland, has declared a specific mushroom, Psilocybe cubensis (Earle) Singer, as being a prohibited "plant" under the Queensland Health Act of l937-l971. Intoxications from the consumption of Psilocybe cubensis were reported as early as l958. Dr. Malcolm C. Hall, formerly of the Canberra Commonwealth Police Force, noted that psilocybine and psilocine were also listed as Schedule 3 drugs in the Tasmanian Dangerous Drugs Order of l965. He pointed out that both of these chemicals were later designated as Schedule l drugs by the International Convention on Psychotropic Substances of l971. This next account is also from an unidentified South Australian drug user who wished to remain anonymous (Southcott 1974). While this person was more then willing to describe his personal usage of these mushrooms, he was extremely cautious about revealing his identity and expressed concern about who might read his story, whether they be friends or law officers. He admitted that he would deny his story if need be. This denial of the use of hallucinogenic fungi by a member of the drug subculture can be compared, in some ways, to the secrecy by which various Indian tribes living in Mexico during the past four centuries have prevented foreigners from exploiting or persecuting their use of psychoactive fungi. In the conquest of Nueva Espana, the Spanish clergy deplored what they considered to be pagan, ritual practices, many of which utilized hallucinogenic plants and mushrooms ceremoniously. The Spaniards harassed, often violently, those whom they caught carrying out these practices. Eventually, the Indians of Mesoamerica, out of fear of persecution, began to hide their use of these plant substances from their Spanish conquerors, and would only communicate their knowledge and use of these substances to one another in secret. Just as the early Christians once tried to hide their Christianity from their peers in ancient Rome, so did several native Mesoamerican tribal peoples hide their use of these magical plants from the Spanish clergy and the Holy Office of the Inquisition. The following account is a good example of the psychological and physiological symptoms of psilocybian intoxication. It also provides insight into this user's own justification for his personal use of psychoactive fungi. "The mushrooms which were prepared in a broth and boiled for about two minutes may be used to induce an extremely powerful hallucinatory trip. When eaten raw the effects can take up to two hours to come on [This time lapse only occurs when fresh food has been consumed prior to the ingestion of fungi], but taken in soup form (or as tea) it can began to occur within five to ten minutes after being eaten. The first noticeable effect is a tingling sensation from head to toe, followed by extreme warmth or cold all through the body. Mild hallucinations began to occur within a quarter of an hour, and become stronger as the trip reaches its peak. This peak can be a terrifying experience for the novice; he does not know what to expect, and can believe himself to have gone insane. This `insanity' can also be pleasurable in many cases and can cause a person to lose all unnecessary fear of things which had previously seemed impossible to bear. Everything material and otherwise is laid in front of you for examination and nothing is beyond human comprehension. In my own opinion and experiences these mushrooms used by persons capable of understanding the tremendous power contained in them can only be beneficial in their effect. I have found them growing in flat-bottomed valleys and on gentle slopes. They thrive in moist, grassy soil and can range in size from a quarter of an inch (approximately 6mm) up to two or three inches (5- 7.5cm) in diameter. [Bob Harris' book, `Growing Wild Mushrooms', published in 1976, contains a photograph of P. cubensis with a cap that is over ten inches in diameter]. In regards to an overdose of these mushrooms, this user feels that: overdosage is not really an accurate term for this condition. It is more an extreme fear of certain things or people which causes 'freakouts'. I have successfully calmed down several people who thought they were on the point of dying. The trip can change from one of fear and hysteria, to one of pure ecstacy in a matter of a second if a person is treated correctly. The police in my opinion [can] cause more bad experiences than all other reasons combined. This is because people strive to have a good trip but the thought of arrest or even goal (jail) can be drastic at the height of a trip's peak. I myself have almost lost all fear of everything I previously feared. I intend to continue the use of these mushrooms and see where it leads me, whether it be a good (lawful) or bad thing, and I am not signing this report on the grounds that it may incriminate myself and other persons." According to Dr. Hall, 60 people in Australia were charged with offenses involving possession or sales of psilocybian mushrooms during l972; however, he also noted that charges against several of these individuals were later withdrawn when no known psychoactive compounds were found in the confiscated specimens of the suspected hallucinogenic mushrooms, and one year later, in a personal communication to R. V. Southcott, Dr. Hall stated that "approximately 74" persons were charged with offenses involving the illicit hallucinogenic mushrooms in Australia during l972. This statement varied somewhat from Dr. Hall's previous claim that 60 individuals were charged with drug offenses related to the psychoactive mushroom use in that year. In any case, by l973, Hall reported that only 27 persons were charged with psilocybian offenses. In 1980, in a special government report on drugs and drug abusers, several prominent Australian citizens expressed their concern about the growing problem of mushroom abuse in Australia (Aust. Govt. Publ. Serv., 1980). "A Queensland school teacher told the commission that because LSD was difficult to obtain and was expensive, people were picking hallucinogenic mushrooms. These could easily be collected around Samford, for example. An informed witness agreed that psilocybine producing fungi were growing in and around Brisbane and mentioned Samford, Ferny Grove, Pinkenba, Dayboro, and Beenleigh. A senior Queensland Police Officer said that `gold top' mushrooms (P. cubensis) were plentiful in the Gold Coast area, but there was no evidence to suggest that they were grown commercially. He said this prohibited plant thrived in the Currumbin and Tallebudgera areas in the wet season and was harvested by drug users."  There is no evidence in the literature indicating that the cultivation of hallucinogenic mushrooms (particularly Psilocybe cubensis), is common among Australian or New Zealand drug users. Recently the author obtained information verifying that mushroom growing kits from the mainland United States are sold through the U.S. mail to both Australian and New Zealand citizens on a monthly basis. Therefore, it may be assumed that some users in Australia and New Zealand do grow these mushrooms at home under clandestine conditions. It is obvious though, that the home cultivation of either Psilocybe, Panaeolus, or even Copelandia species, would not attract the attention of the public or local law enforcement agencies since their growth could be well hidden in home basements, garages, attics, or closets. and not as easily detected as a field of Cannabis.

There is no evidence in the literature indicating that the cultivation of hallucinogenic mushrooms (particularly Psilocybe cubensis), is common among Australian or New Zealand drug users. Recently the author obtained information verifying that mushroom growing kits from the mainland United States are sold through the U.S. mail to both Australian and New Zealand citizens on a monthly basis. Therefore, it may be assumed that some users in Australia and New Zealand do grow these mushrooms at home under clandestine conditions. It is obvious though, that the home cultivation of either Psilocybe, Panaeolus, or even Copelandia species, would not attract the attention of the public or local law enforcement agencies since their growth could be well hidden in home basements, garages, attics, or closets. and not as easily detected as a field of Cannabis.In this same l980 governmental report, Captain B.C. Mundy, Commanding Officer of the Salvation Army in Darwin, Australia presented details concerning the availability of mushroom hallucinogens in the Northern Territory. According to Mundy, 'gold tops' and `blue meanie' mushrooms grew freely in the tropical climate in animal manure and in manured gardens. He referred to an incident where a resident of the Red Shield Hostel in Darwin, who was accused of housebreaking, said he picked 'blue meanies' in the hostel garden and boiled them to make a drink. As a result he was found by the court not responsible for his actions. Captain Mundy explained that the garden had shortly before this incident been treated with fowl manure. This is probably the first reported case of the species C. cyanescens (blue Meanies), being found fruiting from the manure of either chickens, geese, or ducks, rather then from the manure of ruminants (i.e., four legged mammals). It should also be noted here that the youth was not under the influence of inebriating mushrooms prior to his illegal entry at the youth hostel; technically, therefore, he was responsible for his actions. In June of l989, a 23 year-old man from Kelston, New Zealand, appeared in District Court and was convicted of possessing psilocybin. A police spokesman said that they had confiscated approximately 120g of "magic mushrooms" from the suspects home. Mushrooms were found packaged in plastic bags and others were in various drying stages on newspapers placed on the floor. The young man had told the arresting officers that he enjoyed the mushrooms because they "gave him a better outlook on life" (Unsigned, 1989).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|