Mushroom Pioneers

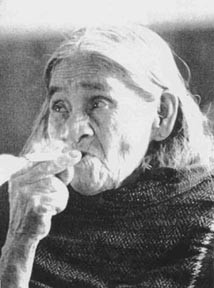

Chapter 5. María Sabina

Saint Mother of the Sacred Mushrooms

|

Fig. 7. María Sabina. |

According to anthropologist Joan Halifax (1979), "For many decades she had practiced her art with the hallucinogenic mushrooms, and many hundreds of sick and suffering people came to her wretched hut to ingest the sacrament as she chants through the night in the darkness before her alter."

Being a kind soul, Doña María welcomed Wasson into her hut and shared the secrets of the sacred mushroom. How could she know that this small, innocent gesture of generosity and kindness would radically change her life and the course of history forever. Despite Wasson's attempts to keep Doña María's identity a secret, the story of the Mazatec witch and her mushrooms of wonder spread throughout the west like wildfire--from the halls of Harvard to the back-beat streets of big town America (when R. Gordon Wasson first wrote of María Sabina and her Veladas in Life magazine (13 May 1957), he referred to her as Eva Mendez, a pseudonym intended to protect her from scalawags and thrill-seekers who might disturb or disrupt her life and those around her).

Wasson's story inevitably piqued the interest of many people. Hoping the mushroom could be a powerful tool in chemical warfare, the CIA sent an undercover agent to Huautla de Jiménez to collect specimens (Marks, 1979). Again, Doña María shared her secret. What else could she do? The mushroom had shown her that the Westerners would never give her peace. Reluctantly she gave in, but with each desecration of the sacred mushrooms she could feel her curing powers fading.

She knew the Westerners would be coming by the dozens (doctors, scientists, thrill-seekers, spiritual pilgrims)all looking for truth, salvation, the curing magic, or even the face of God. Resigned to her fates, Doña María patiently accepted each weary searcher into her home and performed the velada, the all-night vigil, for them. Each time she gave the visitors what they were looking for. Each time she gave away a bit of herself.

Now all that's left of Doña María are memories, memories of the humble woman who inspired the lives of Tim Leary, Ralph Metzner, Andrew Weil, Jonathan Ott, and countless others. Beyond her memory only the mushrooms remain, the tiny magic toadstools Doña María spent her life mastering. Now that she's gone, the only way to find her is through them, through the sacred ceremonies of Mazatec wizards and healers.

Can you make out her face, dark and chiseled with age? Can you hear her songs and chants cutting through the still blackness of night? Her spirit is out there, caught in an endless rainbow spiral of wisdom and beauty. Her ghost is waiting to be heard. Just reach out...

Childhood

Wasson (Estrada, 1976) reported that María Sabina was born on the 17th of March, 1894. According to parish records María was baptized exactly one week after her birth. Her mother María Concepción said her daughter's birth was the day of the Virgin Magdalene (July 22).

According to a verbal account given to Señor Alvaro Estrada, Doña María first consumed the sacred mushrooms with her sister María Ana at an early age (possibly somewhere between the ages of 7 to 9-years-old). Doña María Sabina recalled that she and her sister were out in the woods tending the family's animals when they stopped under a tree to play games in the shade as little children often do when by themselves with no adults around. María looked to the ground and noticed several beautiful mushrooms growing under the tree and realized they were the same mushrooms used by a local curandero Juan Manuel to cure the sick.

Doña María reached down to the earth and carefully harvested several of the mushrooms exclaiming "if I eat you, you, and you, I know that you will make me sing beautifully." She slowly chewed and swallowed the mushrooms, then urged her sister María Ana to do the same. Slowly, young María began to realize that the mushrooms contained a very potent magic, one that she would never forget.

In the following months Doña María and her sister consumed the fungi several times. Once her mother had found her laughing and singing gaily and asked of her "what have you done?". However, she was never scolded for eating the mushrooms because her mother knew that scolding would cause contrary emotions.

According to Joan Halifax (1979) Doña María was eight years old when her uncle fell sick. Many shamans in the surrounding Sierras near her village had attempted to cure him with various herbs, but his condition only worsened. Doña María remembered that the mushrooms she had eaten while playing with her sister had told her to look for them if she ever needed them and that they would tell her what to do when she needed help.

Doña María went to collect the sacred mushrooms and returned to her uncle's home where she ate them. Immediately, Doña María was swept away into the world of the mushrooms. She asked them what was wrong with her uncle and what could she do to help him get well. According to Doña María, the mushrooms told her that an "evil spirit" had entered the blood of her uncle and possessed him. She would have to give him a special herb, but not the same herb which the other shamans and curanderos had previously given him. Doña María then asked the mushrooms where the herbs could be found and the mushrooms told her that there was a place on the mountains where the trees grew tall and the waters of the brook ran pure. In this place in the earth are the herbs which will cure your uncle.

Doña María knew the place the mushrooms had shown her and ran from her uncle's hut to find the herb. Just as the mushrooms had shown her, the herb was there. When she returned to her uncle's home she boiled the herbs and gave them to her uncle. Within a few days, her uncle was cured, and María knew this would become her way of life.

As Doña María grew older she became fully initiated into her role as a sabia (a wise one). She quickly became respected in her village as an honest and powerful sabia, and in her community she was a blessing to those who sought her services. For decades she practiced her healing arts, and countless hundreds of sick and suffering people sought out her magic. Except for her three marriages, where she was expected to care only for her husband, she continued her sacred practices throughout her life.

Being of the Mazatec (Nahua-speaking) people, María Sabina performed her ceremonies in Mazatec (in This Week magazine, Valentina Wasson, 1958 wrote that the ceremony was spoken in Mixtec). Like the pseudonym of Eva Mendez which R. Gordon Wasson gave to María Sabina, this latter report was also published with the intent of keeping her identity a secret from those who would abuse her livelihood.

Like many of the Mazatec shamans, curanderas, and healers, María Sabina referred to the mushrooms as xi-tjo, si-tho or 'nti-xi-tjo, meaning "worshipped objects that spring forth" ('nti=a particle of reverence and endearment, and xi-tjo=that which springs forth). Some Mazatecs refer to the mushrooms by saying "that the little mushroom comes of itself, no one knows whence, like the wind that comes, we know not when or why."

The sacred mushrooms which María Sabina used during an all night velada (vigil) are usually harvested in the evening when the moon is full, although sometimes they are gathered in the day (see footnote 1 at the end of this chapter). Mushrooms gathered in the moonlight may sometimes be harvested by a young virgin.

After the mushrooms are collected they must be taken to a church. There they are placed on an alter to be blessed before the holy spirit. If the virgin who picked the mushrooms comes upon the carcass of a dead animal, one which had died along the path she follows, she must then discard the mushrooms and find a new path back to the field where the mushrooms grew. There she must gather up more fresh mushrooms and then find a new trail leading back to the church, hoping and praying that she will not come across any more dead animals. Once the mushrooms have been consecrated on the alter they are ready for use.

The velada would begin in total darkness so the visions would be bright and clear. After the mushrooms were adorned and blessed by María Sabina, she would slowly pass each one through the swirling smoke of burning Copal incense. The mushrooms are always consumed in pairs of two, signifying one male and one female. Each participant in a ceremony consumes five to six pairs; though more will be given if requested. Because the spiritual energies of the sabia would always dominate the velada, María Sabina would normally consume twice as many mushrooms as her voyagers, sometimes up to twelve pairs.

In the tradition of Mazatec shamans and curanderas, María Sabina would first chew the mushrooms, hold them in her mouth for a while, and then swallow them. The mushrooms should be consumed on an empty stomach and eaten over a 20-30 minute period. She decides who is to take them and the spiritual energies of the sabia always dominate the sessions. These sessions are usually conducted at night, in total darkness so that the visual effects from the mushrooms will be fully effective. A candle or two may be used but is seldom necessary. As the energies of the mushrooms pour themselves into the spiritual voyagers, Doña María would chant, slap, and pound her hands against various parts of her body, creating many different resonant sounds while invoking ancient incantations.

The thumping chants would totally fill the space of her hut and go beyond the walls to the far horizons of infinity. The chants were used to invoke the mushrooms power and varied depending on the various illness or ailment which the healer is called upon to cure (see footnote 2 at the end of this chapter) (Krippner & Winkelman, 1983; also see Aromin, 1973 in Krippner & Winkelman, 1983). Being a devout Catholic her entire life, she would often blend ancient Mazatec rituals with Christian elements, such as the Eucharist of the Catholic religion. When the mushrooms were not in season, María Sabina would employ other sacred plants with Christian rites (see footnote 3 at the end of this chapter).

All accounts of María Sabina attest to the fact that she was indeed a humble and holy woman--a saint. Wasson himself described Doña María as "a woman `without blemish, immaculate, one who has never dishonored her calling by using her powers for evil. . .[a woman of] rare moral and spiritual power, dedicated in her vocation, an artist in her mastery of the techniques of her vocation (Wasson, 1980)." In her village, Doña María was exalted as a "sabia" (wise one), and was known among many as a "curandera de primera catagoria" (of the highest quality) and an "una señora sin mancha' (a woman without stain).

Father Antonio Reyes Hernandez is a man of the cloth, a man with the love of God in him, and the Bishop who resides in the parish of the Dominican church which Doña María belonged to. In 1970, when Father Antonio had just completed his first year as the Bishop of Huautla, Alvaro Estrada (1976) had inquired of Father Antonio if his ecclesiastic elders in the church hierarchy opposed the pagan-like rites of the shamans and sabias in Oaxaca and elsewhere in México as his conquering predecessors had during the last three centuries. Father Antonio replied that "the church is not against these pagan rites--if they may be called that. The wise ones and curer's do not compete with our religion. All of them are very religious and come to our mass, even María Sabina. They don't proselytize; therefore they aren't considered heretics, and it's not likely that any anathema's will be hurled at them."

Father Antonio never admonished or condemned her for her work in the village. He was aware that her rituals and practices had been handed down to her through the ages from her ancestors. He also knew that her services were valid treatments for those who sought her shamanic talents. Father Hernandez always recognized her work with the sick and suffering as the mark of a true Christian--one willing to help the less fortunate. Although he knew that Doña María used the mushrooms and pagan practice to heal and cure, he also understood that María Sabina's nature was not of a demonic spirit, "nor was it" satanic or even heretic. He appreciated her spirituality and treasured her work as a long termed good standing member of his church.

A Bishop interested in experiencing the visionary effects of the mushrooms came to María seeking guidance. However, he was turned away since it was not the season for the mushrooms and there were no mushrooms available for a ceremony. The Bishop had asked María Sabina if she would teach her children her talents. María Sabina told the bishop that her talents could not be taught to others but could only be achieved by those whose wisdom had been already naturally attained. However, it is said that before her death in 1985, Doña María spent most of her final years teaching others her talent in the communication of the mushrooms (Krippner (1987 [1983]).

As Doña María believed in the power of Christ, so she also believed in the power of the mushrooms. She gave of herself to her church and likewise to the mushrooms. While working for the church, her mass was spoken in Latin and her chants were always spoken in Mazatec, and it should be remembered that although Doña María was unlettered she was not illiterate.

Doña María was quick to notice that Wasson and his friends, being the first foreigners to (seek) out the 'saint children' (mushrooms), had no sickness or illness to cure. They came only out of curiosity, or to find God (Estrada, 1976). Before Wasson and the others strangers came to Huautla, the mushrooms had always been used to treat the sick. Doña María foresaw the diminishing effects in her ability to perform her duties. She claimed that as more outsiders used the mushrooms for pleasures, or "to find God," the magic of the mushrooms slowly ebbed from her spirit. Her energy, and the energy of the mushrooms, was slowly fading away.

While María Sabina felt this debasement of her powers and relationship with the mushrooms was caused by the young foreigners who frivolously sought out and abused the sanctity of the sacred mushrooms, it should be noted that seeking and finding one's own god may also be a cure for many of mankind's psychological ills, woes, and faults.

The Coming of the Foreigners

In the beginning, the first travelers who came to Oaxaca in search of the sacred mushrooms were polite and kind to María Sabina. They displayed mutual respect for her personage. Many came bearing gifts and pesos for her services. Doña María received many people (young and old) into her home and performed for them the sacred ceremonies of her ancestors. One of the greatest gifts one could present her with for her services were photographs of her and her family. Some travelers would offer her gifts of no value and many gifts she considered useless. One tourist offered her a large dog in payment for her time, but she refused. She was too poor to afford feeding the animal. Although poor, María Sabina was spiritually enriched.

Doña María had also been widowed twice in her lifetime and once one of her sons had been brutally murdered before her very eyes. She claimed to have witnessed the crime in a vision prior to its happening. This supports the Wasson's assertions that the mushrooms have telepathic properties. In 1984, María Sabina had found a third husband.

Her three room home in Oaxaca where Doña María performed her ceremonies was created of mud with a straw thatched roof and a dirt floor. The interior of her humble dwelling whose walls were crumbling with age had uneven earthen floors which were almost barren of furniture except for the simplest alter. A candle provided the only light since there was no electricity. On a few occasions she was presented with a mattress or two, but she rarely accepted gifts beyond the value of her daily needs.

After Wasson published literature on his rediscovery of an ancient practice which utilized hallucinogenic mushrooms ritualistically in Oaxaca, many young foreigners from the United States, Canada, Europe and South America, began their long treks and tedious pilgrimages into Mexico. Soon Doña María took notice that many native Indians and Mexicans alike were debasing her customs by peddling mushrooms to the tourists in order to feed themselves and their families. During this period, many came seeking the mushrooms and many came only to be turned away.

By 1960, María Sabina realized that she was known the world over. This new found fame brought her much grief, and the agony it caused her soul was evident in her eyes and face. It brought turmoil and profanation to her village and upon her work.

The lack of respect and the total disrespect which the foreigners displayed towards her "saint children" shook the very foundations of her wisdom, strength, and world. Like the ancient mysteries of the "temple of Dionysus" where silence of the ancient rites was golden, María Sabina claimed that before Wasson came, "nobody spoke so openly about the `saint children'. No Mazatec before ever revealed what he or she knew about this matter (Estrada, 1976)".

After Wasson had attended his first voyage with her, every one seemed to know who she was and what she did.

When Wasson was first introduced to María Sabina in 1955, it was only because of an introduction by her friend Cayetano (Wasson, 1957; Wasson, 1980; Allen, 1987). He was a trusted friend, and María felt that Cayetano's requesting her to meet with the stranger who had traveled from afar in search of a "sabia" was harmless. Upon first meeting Wasson, María Sabina believed him to be a sincere and honest man, and felt that he would respect her ways and never bring shame to her world. Although she cautiously accepted Wasson when Cayetano approached her, she would later accept many into her home, and there were also many whom she would turn away.

María Sabina placed her trust in Wasson and his friends, especially when she allowed them to tape and photograph her during an all night mushroom velada. She gave Wasson and Alan Richardson, his photographer, permission to tell her story to others. Doña María hoped that Wasson would not profane her image nor divulge her anonymity to the world in an improper manner. Because Doña María neither read nor wrote (her language has no written words) she would never fully know exactly what Wasson had written of her life.

By 1960, Doña María had decided that if "foreigners come to her without any recommendations [whereas Wasson had one], she would of course still show them her wisdoms" (Wasson, 1980).

During the 1967 summer of love, many drugs and rampant drug use spread from out of the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco into the main stream continental United States of America. Many young hippie types and college students soon traveled to México in search of the magic mushroom which they had read about or heard about from their friends (Swain, 1962; Finkelstein, 1969; Lincoln, 1967; Sandford, 1973; Weil, 1980).

Doña María soon began to understand the breadth of her fame when over the years she remembered the pilgrimage of "the young people with long hair who came in search of God" but lacked the respect for the mushrooms and greatly profaned them.

Later, Doña María realized that "the young people with long hair didn't need [her] to eat the little things." She said that these "kids ate them anywhere and anytime [they could find them], and they didn't respect our customs." Doña María also claimed that "whoever does it [mushrooms] simply to feel the effects can go crazy and stay that way temporarily, but only for a while."

Wasson recognized the traditional values of the religious motivations of the Mazatec shamans and sabias, explaining that "performing before strangers is a profanation and that the curandera who today, for a fee will perform the mushroom rite for any stranger is a prostitute and a fakir" (Metzner, 1970), yet María Sabina did perform rituals for strangers, sometimes for a fee and sometimes not. At times, she had been known to charge for services which she used to provide for free.

At one point an American tourist once ate too many mushrooms and completely flipped out. He caused "much turmoil" and anxiety in an otherwise once quiet and peaceful community. Another tourist, with a live turkey dangling from his mouth, ran stark raving mad through the streets of Huautla. This incident necessitated intervention by local policia who apprehended him before he could do harm to himself or others. This incident, along with several others, soon led to the expulsion of thousands of long haired thrill seekers from Mexico.

The actions of these young people created many scandals. With the influx of drug-oriented young people, local authorities began to prohibit the use of mushrooms. By 1976, the thousands of foreign invaders began to drastically diminish, allowing the federales to slowly move out of the area. To the native peoples of Oaxaca, the bad elements had finally subsided and peace had once again returned to the village.

Throughout the years Doña María had been hassled many times by local government officials because of her use of the sacred mushrooms with the foreign intruders.

On several occasions she was arrested and jailed for her activities and on one occasion her home was burnt to the ground. A journalist who interviewed her in 1969, tried to intervene for her in this matter. He personally requested that the governor of Oaxaca "leave in peace the most famous shamaness in the world, whom anthropology and escapism have ruined" (Estrada, 1976).

May the Force be With You

|

Fig. 8. María Sabina. |

Doña María believed in the sacred force of the mushrooms with the same enthusiasm that many people came to believe in "the Force" of George Lucas and Luke Skywalker. As the years passed since Wasson first came to Huautla de Jiménez, Doña María felt the force of the mushrooms diminish within her spirit. Doña María realized that with the coming of the white man, the mushrooms were losing their meaning. Doña María claimed that "before Wasson, I felt that the `saint children' elevated me. I don't feel like that anymore. The force has diminished. If Cayetano had not brought the foreigners...the `saint children' would have [probably] kept their powers. From the moment the foreigners arrived, the `saint children' lost their purity. They lost their force; the foreigners spoiled them. From now on they won't be any good. There is no remedy for it."

This revelation from María Sabina most assuredly rings of the truth. The debasement of the mushrooms by casual thrill-seekers is widespread throughout the planet. Apolonio Teran, a fellow sabio (wiseman) was once interviewed by Alvaro Estrada. Estrada asked Apolonio about the breach of sanctity of the mushrooms by debasement wondering if the mushrooms were still considered to be a sacred and powerful source of medicine.

Apolonio claimed that "the divine mushroom no longer belongs to us [the Indians of Mesoamerica]. It's sacred language has been profaned. The language has been spoiled and it is indecipherable for us...Now the mushrooms speak NQUI LE [English]. Yes, it's the tongue that the foreigners speak...The mushrooms have a divine spirit. They always had it for us, but the foreigners arrived and frightened it away..." Later Wasson (1980) agreed that "since the white man came looking for the mushrooms, they have lost their magic." This could mean that the magic is gone forever among the shamans and native peoples who worship them.

Wasson believed that Doña María's words rang of truth. In exemplifying her wisdom, Wasson stated that "a practice carried on in secret for three centuries or more has now been aerated and aeration spells the end (Estrada, 1976)."

Before Wasson's death (December, 1986), he felt that he alone was responsible and accountable for what must surely be a sad and tragic end to a culture whose traditions and customs involving the sacred use of teonanácatl spanned and flourished majestically for almost three millennia. It now appears that the use of mushrooms among native peoples of Mesoamerica are in their final stages of extinction. Soon the cultural use of mushrooms and other sacred plants could vanish from the face of the earth.

Wasson's eloquent approach in presenting María Sabina's world to the public is without a doubt, beyond reproach. He presented a most unique tale of María Sabina and her sacred mushrooms. His writings took us where no man had gone before and he presented to the world her story as no other person would have. Wasson brought María Sabina and her world into view of the public eye. He told of her chants, her way of life, her reasoning, and of her magic with her fellow village members, all who visited her seeking her advice and divination. Wasson orated her virtues with the highest respect and the finest regards and what he put to paper was only the truth as she revealed it to him and as he first saw and heard it.

Wasson knew that María Sabina was relevant to the balance of nature within her community. He held an extreme profound reverence for the woman and her work. At the same time he displayed features of her spirituality without bringing shame upon her heritage. He presented her to the world with an integrity that brought enchantment with what he wrote. Wasson's discoveries in Mesoamerica and his integral interpretations are what María Sabina would have written and described if she had been able.

Because of Wasson's intrusion into her life and the myriad who followed, a part of María Sabina's world and way of life was taken away. However, the vast treasures of ethnomycological knowledge and wisdom which Wasson extracted from her world became public only because she shared it with the outsiders. This knowledge will now remain a part of history because it was recorded by an honorable man who cared about what he had observed, experienced, and wrote of.

María Sabina was many things: an earth woman, a mother, a sabia, a poet, a healer, a curer, a believer, an achiever, and a curandera who stood at the very edge of her universe and glimpsed the secrets and meaning of life. Doña María had shared her secrets of magic and plant knowledge with the outside world. Only through hope and prayer will the benevolence she provided to the world be fully understood and appreciated. Through the pursuance of R. Gordon Wasson's persistency in following his dream of the trail of the magic mushrooms, Doña María has truly presented mankind with a magical key (mushroom) concerning some plausible answers surrounding some of the mysteries of our religious beginnings and maybe the origin of the earth.

Doña María may be gone, but her spirit and her wisdom still remain. Reach out and take the wisdom she was so willing to share. Take it with care and share it with love and respect. Can you see her face in the dark? Can you hear her chanting?

Notes

1). María Sabina used many different species of the sacred mushrooms for divination. She preferred Psilocybe mexicana Heim, the preferred species of the Mazatec shamans. However, the mushrooms which she shared with R. Gordon Wasson and Alan Richardson were Psilocybe caerulescens var. mazatecorum.

2). The sacred mushrooms are usually consumed when fresh but may sometimes be served when dried. In pre-Columbian México the mushrooms were served and eaten with chocolate and/or honey. A trait left over from the times of the Aztec priests, a cultural tradition handed down through centuries of use by their ancestors. In some regions like Juxtlahuaca, the Mixtec shamans grind the mushrooms into a fine powder and brew a tea with the ground material.

Metzner (1970) reported that "in the land of the Mixe (Mijes) there are no curanderas. Most of the Mixe know and share the secret of the mushrooms and how to use them. One might take the mushrooms alone but will always have an observer present, to help guide him or her in their journey. The reason one might seek the mushrooms are medical and divinatory: to find a diagnosis and/or cure for an otherwise intractable condition; to find lost objects, animals or people; to get advice on personal problems or some great worry."

Although María Sabina had gracefully preserved within her the power and wisdom derived from her relationship with the mushrooms, she only used them for good purposes. She also incorporated old traditions, blending them with certain Christian values and ideologies to divinate a particular situation, thereby diagnosing it correctly for the person in need of healing.

Singer and Smith (1958) believed that "the religious healing ceremonies of the Mazatec are also directed by the curanderos [or curanderas], but more emphasis is given to the revelations obtained by the intoxicating persons, so that the use of the mushrooms in Huautla is at least partly divinatory rather then medical." Metzner (1970) felt that "the use of mushrooms for the [sole] purpose of divination is accepted as a matter of fact. Demonstrations of its capacity to bring about altered states of consciousness combined with brilliant kaleidoscopic visions of glorious colors and patterns have been convincingly made." Aguirre-Beltran (1955) claimed the healer (whether shaman or curandera) "looked not at the context of what it was in these plants that make them do their magic, but felt that the Indians' thoughts on these plants possessed two different aspects in their use in treatment:

1) the mystical force that the plants projected into ones mind; and

2) the actual diagnostic power that the use of the plant brings out."

Beltran was positive that the "sacred herbs, deities in themselves, act by virtue of their mystical properties; that it is not the herb itself that cures but the divinity, the part of the divinity or magic power with which it is imbued."

In considering the outcome of these ancient pagan practices in traditional societies, we cannot forget that in María Sabina's world the velada and mushrooms that she feeds upon provide the guideposts to her spiritual existence. Doña María had already foreseen the diminishing effects in her ability to perform her duties as the mushrooms became known to the outsiders. She claimed that the more outsiders who used the mushrooms for pleasure or "to find God" caused the magic of the mushrooms to slowly ebb from her spirit. Her energy and the energy which were within the mushrooms was slowly fading away. Metzner (1970) wrote that the "practice which she employed was all that remained among a primitive and illiterate people today of a practice which was once so widespread throughout the mighty and powerful [Aztec] empire" that 300 years ago, a catholic conqueror named Cortez and a hoard of conquistadors almost succeeded in obliterating from the face of the earth any knowledge pertaining to their use and existence.

3) When the mushrooms are not in season, Mazatec shamans and curanderas (including María Sabina) employ several other common psychotropic plants for divination.

One such plant is Salvia divinorum, a member of the mint family which is rich in essential oils. Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann (1980) reported that it was a plant used ceremoniously by María Sabina. Mazatec shamans and sabias refer to this plant as "Hojas de la Pastora" (leaves of the shepherdess). Doña María Sabina referred to it as "la hembra" (the female) (Wasson, 1962b). Salvia's divinatory powers can be experienced by rolling twelve to sixteen mature leaves into a plug and holding it between the cheek and gum for fifteen minutes. Profound visual effects will be noticed with eyes closed or in total darkness. Dried Salvia leaves can also be smoked for milder effects.

When the Salvia herb is not available for use in divination, the Mazatecs employ two different species of Coleus found in Oaxaca. Coleus pumilus is referred to as "el macho" (the male). Two other varieties of Coleus blumi are referred to as (1) "El nene" (the children) and (2) "el ahijado" (the godson). The psychoactivity of Coleus is debated.

Another popular plant, a perennial, is the morning glory Rivea corymbosa, whose seeds contain lysergic acid amides. Also known as ololiuhqui. In Oaxaca, Mazatec shamans refer to the seeds as "Semillas de la Virgen" (seeds of the Virgin). 50 to 300 ground seeds are soaked in cold water for 1 to 3 days and the filtered liquid is consumed in the evening. However, María Sabina had never used these seeds in any of her ceremonies.

|

Image 5: The Equadorian Shroom Graphic Design by John W. Allen |