Cardboard Boxes All the Way Down

Exploring the archives of the counterculture

Aug 2016

Originally published in Erowid Extracts #29

Citation: Erowid. "Cardboard Boxes All the Way Down". Erowid Extracts. Aug 2016;29:12-15. Online edition: Erowid.org/library/library_article1.shtml

|

|

Before taking a trip to New York City in February, I made sure to set up a visit with a bunch of boxes at the New York Public Library (NYPL). These hundreds of boxes contain the Timothy Leary papers, 1910-2009, which the Manuscripts and Archives Division purchased in 2011 and made available to researchers two years later. As a PhD working in the field, it was easy for me to get access to the archive. If you are an independent researcher and have a good spiel about a project, it's not too tough to get your hands on these things. And if you are in New York, you should!

The Manuscripts and Archives Division is housed in a pleasant, old-school scholarly reading room, with plush chairs and book-lined walls. I could only request a few boxes from the vault at a time, and staff held those behind the counter, doling them out one by one. Pencils only in the room, but I was allowed to take pictures of whatever I wanted.

"What's the difference between an archive and a pile of moldering cardboard boxes in a shed in the backyard?"

|

Leary in the '70s

Given my current research on "high weirdness" in the seventies, my main interest was in Leary's second prison stint, when he received what he called the "Starseed Transmissions". In a series of chapbooks and self-published texts, Leary turned his back on the hippie-Hindu mysticism of his '60s persona and embraced a futurist, proto-Mondo 2000 worldview of sci-fi, spacefaring techno-optimism. In the boxes associated with this era, I found letters and texts that, though of only moderate interest in themselves, gave a strong sense of the range of Leary's interests and attitudes at that time. This material included letters that made it clear to me that Leary had not really become a New Age channeler of E.T. information but was, once again, crafting a tactical mask.

|

I realized then that while the Leary papers are obviously a gold mine to students of the old rascal, they are just as valuable as an impressionistic record of that counter-cultural era. Like a magnet, Leary attracted all sorts of attention, and because he was vain about publicity, keeping all the records of his ego's successful course through the world, researchers like me can now pore through a cornucopia of "signs of the times".

|

|

|

|

|

Big Data

The exhilaration of delving into archives is often coupled with a state of information overload all too familiar today, a kind of claustrophobia, indecision, and exhaustion. What objects are the most valuable? Is this a key? The mind, even a mind used to thinking in terms of historical trends, boggles before so much raw material, so many questions that could be asked, so many rabbit holes to tumble down.Archives are like the original "Big Data". Once they are gathered, the question becomes: what kinds of value can be generated from the material? This value is in turn directly related to what kind of questions one asks. In a sense there is always more than one archive, because what the archive "contains" reflects the different sorts of research projects (and wayward serendipitous wanders) that are brought to it.

Piles of Boxes

But what's the difference between an archive and a pile of moldering cardboard boxes in a shed in the backyard? I got to contemplate this question immediately after returning to the Bay Area from New York. I met up with my pal R. John Williams, a professor of English at Yale, and we went to visit a fellow in Sonoma County (north of San Francisco) who possessed such a shed. The boxes in question had belonged to a curious character named Kurt von Meier (1934-2011), a groovy pot-smoking art historian, renegade, and polymath who cut a fascinating swath through California head culture in its glory years, touching on Esalen, multimedia happenings, Tibetan Buddhism, and first-wave California cuisine.Interested in von Meier's connections with the British intellectual George Spencer-Brown, author of Laws of Form (1969), Dr. Williams was also on the hunt for von Meier's obscure mid-'70s, Castaneda-esque novel The OMasters — an unpublished text he had learned about after sifting through a different archive in Champaign, Illinois.

This was not the New York Public Library. There was no catalog. Bugs, mold, and dust infested the boxes. It was a good lesson in the overwhelming materiality of analog archives, and their capacity to generate a "small infinity" of one damn thing after another. We didn't have enough time or resources to be anything close to systematic, but our scattershot efforts still bore fruit. We found moldy reel-to-reels with famous conversations recorded on them, a smattering of informative press clippings, and a possibly full manuscript copy of The OMasters. We also discovered a package addressed to Andy Warhol and stuffed with photographs of early Velvet Underground sessions. Amazing, but where did it fit? So back into a box it went. One thing that is clear about archives: you may get the answers you are looking for, but you always leave with more questions.

Erowid's Cardboard Boxes

Over the years, Erowid Center has received a number of collections of physical documents, books, ephemera and recordings. This is an important reminder of the mission of Erowid, which is not just to be an online resource for the most up-to-date information on psychoactive compounds, but to create and maintain a public "cultural memory" of psychoactive and psychedelic plants and chemicals, and the people and societies that have been changed by their encounters with them.This sort of archival work is particularly important because many of the mainstream institutions that form and create archives have, for the most part, ignored countercultural materials, and particularly ones associated with drugs. This is changing of course, but Erowid Center has and will continue to play an important role in the archiving of modern and ancient psychoactive culture.

One of the things that can define an archive is whether it is capable of absorbing other people's moldy old boxes of crap and transforming them into useful material. While lots of independent researchers, publishers, and heads have developed amazing personal collections over the years, few families or estates have the resources to maintain these materials in the wake of mortality. Often the collections get broken up and sold or, worse, lost, burned, or tossed away. To prevent this, some estates find institutions such as university libraries to house the materials. Or the collectors themselves decide to donate them before their death.

Erowid has received and processed some noteworthy materials, including large collections of papers belonging to Albert Hofmann and Myron Stolaroff. In both these cases, Erowid scanned the papers and, once they were digitized, returned the physical artifacts. Erowid has also received physical collections from researchers, publishers, and enthusiasts, and presumably more will keep coming in. Indeed, now that the baby boomer generation has hit its sunset years, many people will be thinking about what to do with their collections; hopefully, some of the heads will remember Erowid!

Recently, I visited the temporary site of the Erowid Library. Fire and I went through some of the donated boxes that were piling up. The experience reminded me at once of the exhilaration and exhaustion associated with the other archives I have been to. One task was to process a dozen or so boxes of books that had belonged to Bob Wallace, a software pioneer, activist, and philanthropist who co-owned Mind Books, a mail-order bookstore offering publications about psychoactive plants and compounds. They had already been cherry-picked for their more rare and expensive items, which made them less exciting. But the thing about an archive is that it is tough to separate wheat from chaff, since part of the point is to keep materials that seem like noise, but that may provide signal to future researchers who are following questions and agendas we can't yet imagine.

So, for example, the boxes contained dozens of sociological books from the seventies and eighties about the drug scene, some written by academics with an eye towards a popular audience, and others of a more technical nature. In some ways these texts, devoid of colorful writing or personal detail, are incredibly dull and seemingly useless for people interested in these questions today. But for historians tracking the way that psychoactive substances get re-imagined and redescribed over time, these boring books can actually be worthwhile--not only as a window into the drug scene of the times, but, perhaps as importantly, into how professionals thought about and wrote about these scenes.

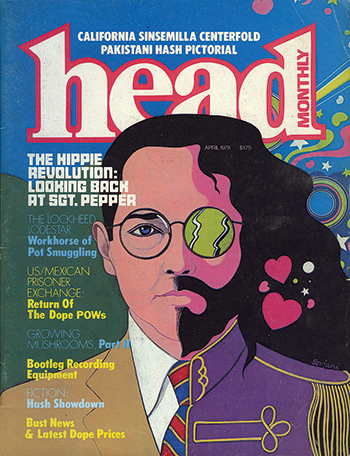

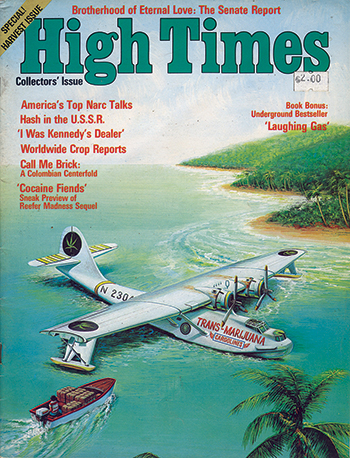

The most fun I had during my day of archive spelunking at the Erowid Center Library was going through old issues of High Times magazine. Erowid had been gifted several large sets of the magazine, and Fire and I carefully compiled these different collections into one master set, culling the duplicates for other uses and putting everything in order. I am enough of a nerd to enjoy the cataloging process itself, but I was really interested in the issues from the seventies.

"You may get the answers you are looking for, but you always leave with more questions."

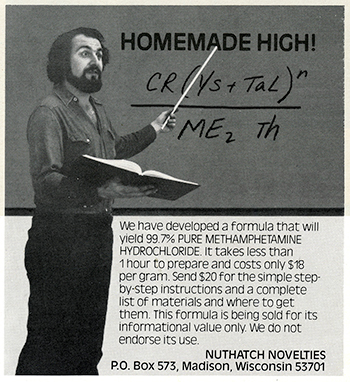

The sixties and seventies were good years for magazines, and High Times had some great writers like Glenn O'Brien and Andew Weil, and lots of editorial sass. But half the fun lies in the ads. After all, the magazine wouldn't be there if it wasn't making money, and it was making money because people had a lot of drug-related materials to advertise and sell. These included a hilarious number of porno pipes, mannitol and other cocaine cutting agents, erotic coloring books, rolling papers, coke spoons, scales, t-shirts (with bra-free models, natch), and five-foot model pyramids made of opaque vinyl. The sly exuberance of many of the ads reflected a hedonism at once unhinged and strangely innocent in its pleasures.

Alongside the paraphernalia, however, the magazine was also more directly keyed than I would have thought to the much larger and very real world of the explicitly illegal drug trade. The round-up of news on busts and DEA activity seemed very thorough, while the Trans-High Market Quotations diligently collected worldwide prices for cannabis and any number of other desirable compounds, including Quaaludes, crystal meth, and PCP. Fully illustrated articles on the best smuggling planes and a myriad of true life tales in exotic locales suggested that, along with being a mix of Rolling Stone and National Lampoon, the magazine was also a bit like a stoned Soldier of Fortune, and that the true hero of 1970s drug culture was not the grower or dealer, but the globe-trotting smuggler.

The Next Box

It's always nice to bank on future thrills, and I am happy that there are still boxes at the Erowid Center Library that remain unprocessed and uncatalogued. On top of some of the intellectual challenges associated with finding the best way to organize and sift through these materials, there's always the possibility of coming across rare and mind-blowing cherries to pick. An unpublished manuscript on a vital topic! A substantive letter with a famous signature! Lab specs! Drug porn! And if, instead, the material turns out to be dreadfully boring, you can always just shelve it. Next!So, for the sake of cultural memory (and my own future thrills), I urge you to keep the Erowid Center Library in mind. If you own or know of drug-related archives--however small--please consider the Erowid Center Library when it comes time to pass them on. (This includes not only books, magazines, and articles, but what archivists call "ephemera": posters, cards, ads, fliers, etc.) Or make a financial contribution to Erowid's digitizing efforts, which help ensure online access to such archives. Authors can also donate the right for Erowid to publish out-of-print books or articles online, even, or especially, texts now forgotten by history. Because history doesn't really forget--it just sticks everything in a box somewhere.

Image Credits #