Golden Guide: Hallucinogenic Plants

pages 71 to 80

.

Contents...1-10...11-20...21-30...31-40...41-50...51-60...61-70...71-80...81-90

91-100...101-110...111-120...121-130...131-140...141-150...151-156...Index

CHEMICAL INVESTIGATION of the Mexican mushrooms was difficult until they could be cultivated. They are almost wholly water and great quantities of them are needed for chemical analyses because their chemical constitution is so ephemeral. The clarification of the chemistry of the Mexican mushrooms was possible only because mycologists were able to cultivate the plants in numbers sufficient to satisfy the needs of the chemists. This accomplishment represents a phase in the study of hallucinogenic plants that must be imitated in the investigation of the chemistry of other narcotics. The laboratory, in this case, became an efficient substitute for nature. By providing suitable conditions, scientists have learned to grow many species in artificial culture.

A laboratory culture of Psilocybe mexicana, grown from spores, an innovation that speeded analysis of the ephemeral mushroom.

(After Heim & Wasson: Les Champignons Hallucinogenès du Mexique)

Cultivation of edible mushrooms is an important commercial enterprise and was practiced in France early in the seventeenth century. Cultivation for laboratory studies is a more recent development.

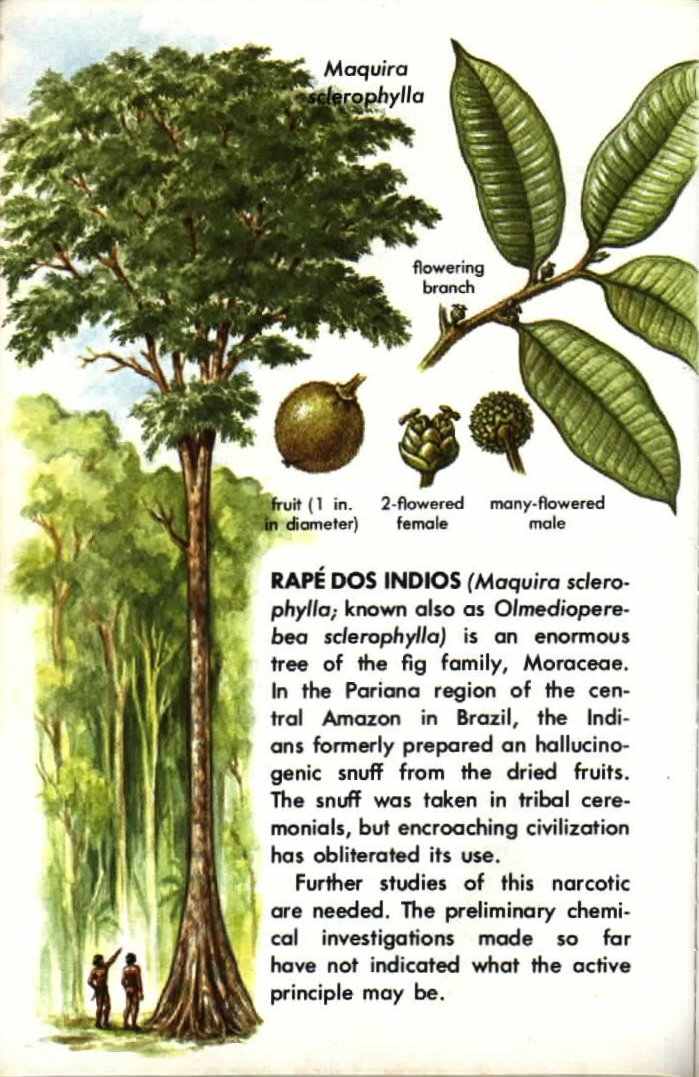

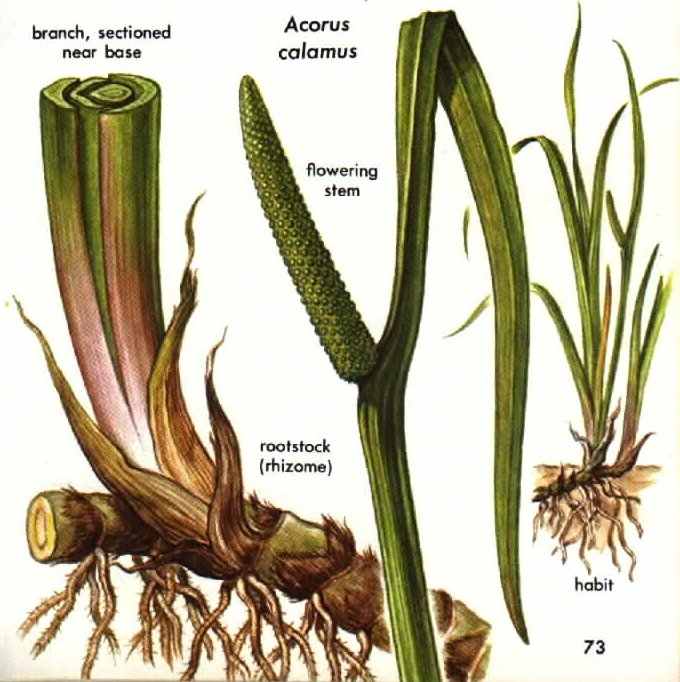

SWEET FLAG (Acorus calamus), also called sweet calomel, grows in damp places in the north and south temperate regions. A member of the arum family, Araceae, it is one of two species of Acorus. There is some indirect evidence that Indians of northern Canada, who employ the plant as a medicine and a stimulant, may chew the rootstock as an hallucinogen. In excessive doses, it is known to induce strong visual hallucinations. The intoxicating properties may be due to a-asorone and ß-asarone, but the chemistry and pharmacology of the plant are still poorly understood.

Colombian Indians using a snuffing tube fashioned from a bird bone.

VIROLAS (Virola calophylla, V. colophylloidea, and V. theiodora) are among the most recently discovered hallucinogenic plants. These jungle trees of medium size have glossy, dark green leaves with clusters of tiny yellow flowers that emit a pungent aroma. The intoxicating principles are in the blood-red resin yielded by the tree bark, which makes a powerful snuff.

Virola trees are native to the New World tropics. They are members of the nutmeg family, Myristicaceae, which comprises some 300 species of trees in 18 genera. The best known member of the family is Myristica fragrans, an Asiatic tree that is the source of nutmeg and mace.

In Colombia, the species most often used for hallucinogenic purposes are Virola calophylla and V. calophylloidea, whereas in Brazil and Venezuela the Indians prefer V. theiodora, which seems to yield a more potent resin.

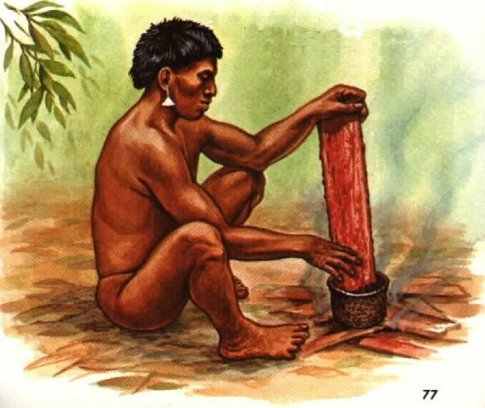

AN INTOXICATING SNUFF is prepared from the bark of Virola trees by Indians of the northwestern Amazon and the headwaters of the Orinoco. An anthropologist who observed the Yekwana Indians of Venezuela in their preparation and use of the snuff in 1909 commented:

"Of special interest are cures, during which the witch doctor inhales hakudufha. This is a magical snuff used exclusively by witch doctors and prepared from the bark of a certain tree which, pounded up, is boiled in a small earthenware pot, until all the water has evaporated and a sediment remains at the bottom of the pot.

"This sediment is toasted in the pot over a slight fire and is then finely powdered with the blade of a knife. Then the sorcerer blows a little of the powder through a reed . . . into the air. Next, he snuffs, whilst, with the same reed, he absorbs the powder into each nostril successively.

"The hakudufha obviously has a strong stimulating effect, for immediately the witch doctor begins to sing and yell wildly, all the while pitching the upper part of his body backwards and forwards."

Strip of bark from Virola tree, showing oozing resin.

Among numerous tribes in eastern Colombia, the use of Virola snuff, often called yakee or parica, is restricted to shamans. Among the Waiká or Yanonamo tribes of the frontier region of Brazil and Venezuela, epena or nyakwana, as the snuff is called, is not restricted to medicine men, but may be snuffed ceremonially by all adult males or even taken occasionally without any ritual basis by men individually. The medicine men of these tribes take the snuff to induce a trance that is believed to aid them in diagnosing and treating illness.

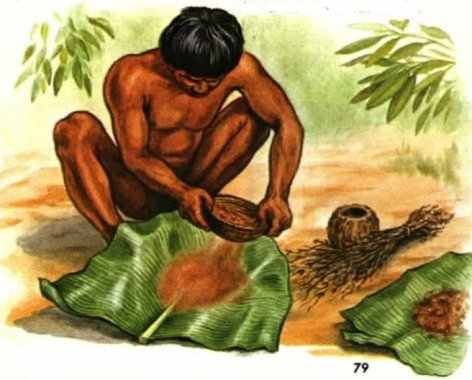

Although the use of the snuff among the Indians of South America had been described earlier, its source was not definitely identified as the Virola tree until 1954.PREPARATION OF VIROLA SNUFF varies among different Indians. Some scrape the soft inner layer of the bark and dry the shavings gently over a fire. The shavings are stored for later use. When the snuff is needed, the shavings are pulverized by pounding with a pestle in a mortar made from the fruit case of the Brazil- nut tree. The resulting powder is sifted to a fine, pungent brown dust. To this may be added the powdered leaves of a small, sweet-scented weed, Justicia, and the ashes of amasita, the bark of a beautiful tree, Elizabetha princeps. The snuff is then ready for use.

Waiká Indian scraping Virola resin into pot, preparatory to cooking it.

Dried Justicio leaves are ground before being added to snuff

Other Indians fell the tree, strip off and gently heat the bark, collect the resin in an earthenware pot, boil it down to a thick paste, sun-dry the paste, crush it with a stone, and sift it. Ashes of several barks and the leaf powder of Justicia may or may not be added.

Still other Indians knead the inner shavings of freshly stripped bark to squeeze out all the resin and then boil down the resin to get a thick paste that is sun-dried and prepared into snuff with ashes added.

The same resin, applied directly to arrowheads and congealed in smoke, is one of the Waika arrow poisons. When supplies of snuff are used up in ceremonies, the Indians often scrape the hardened resin from arrow tips to use it as a substitute. It seems to be as potent as the snuff itself.A SNUFF-TAKING CEREMONY is conducted annually by many Waiká tribes to memorialize those who have died the previous year. Endocannibalism comprises part of the rite; the ashes of calcined bones of the departed are mixed into a fermented banana drink and are swallowed with the beverage.

Waika Indian sizing ground Justica leaves to make fine powder

for additive to Virola snuff.

The ceremony takes place in a large round house. Following initial chanting by a master of ceremony, the men and older boys form groups and blow huge amounts of snuff through long tubes into each other's nostrils (p. 74). They then begin to dance and to run wildly, shouting, brandishing weapons, and making gestures of bravado. Pairs or groups engage in a strange ritual in which one participant thrusts out his chest and is pounded forcefully with fists, clubs, or rocks by a companion, who then offers hisown chest for reciprocation. Although this punishment, in retribution for real or imagined grievances, often draws blood, the effects of the narcotic are so strong that the men do not flinch or show signs of pain. The opponents then squat, throw their arms about each other, and shout into one another's ears. All begin hopping and crawling across the floor in imitation of animals. Eventually all succumb to the drug, losing consciousness for up to half an hour. Hallucinations are said to be experienced during this time.

Waika round house in clearing in Amazon forest.